From SPPG to PPPK: The Dynamics of Program-Based Staffing in Indonesia’s Civil Service Reform

The government’s decision to appoint personnel from the Nutrition Fulfillment Service Unit (SPPG) as Government Employees with Work Agreements (PPPK),…

What if something as ordinary as the seafood on our dining tables carried an invisible danger?

While public attention was still fixed on the Free Nutritious Meal (MBG) program controversy, another, quieter storm began to rise — an alleged case of radioactive contamination in frozen shrimp from Cikande Industrial Estate, Serang, Banten.

The alarm was first sounded by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which detected traces of Cesium-137 (Cs-137) — a radioactive isotope — in shrimp exported from PT Bahari Makmur Sejati (BMS), located within the Cikande complex. The finding prompted a swift investigation by Indonesia’s Nuclear Energy Regulatory Agency (BAPETEN) and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK), both of which confirmed the presence of Cs-137 residues in the surrounding industrial area.

This discovery quickly escalated from a trade issue into a national crisis touching on environmental security, food safety, and public health. In an era of rapid industrialization, it became a chilling reminder that the greatest dangers may no longer come from visible pollution — but from invisible radioactive traces that slip through the cracks of weak industrial oversight and waste management.

Cesium-137, commonly used in medical radiotherapy and industrial measurement tools, should never appear in the food chain. Its detection near food-processing facilities exposed how fragile our safeguards remain. Cs-137 emits beta and gamma radiation, has a half-life of roughly 30 years, and prolonged exposure can lead to DNA mutation, cancer, and even death.

Soon, the focus of coverage shifted from the exported shrimp to the search for the contamination source. Investigators suspected the radiation originated from metal-smelting activities or scrap-metal waste containing industrial residues. Tests revealed traces of Cs-137 in several factory components, including blowers and ventilation ducts. Later reports pointed to PT Peter Metal Technology (PMT) as the likely source of the contamination.

For many Indonesians, this was more than sensational news — it was a terrifying revelation that questioned both food security and public trust in government institutions. The incident also opened a broader debate on environmental accountability, transparency, and crisis communication in Indonesia.

The story first broke in early September 2025, when the FDA issued its official report. Within days, Indonesian media outlets picked it up, and headlines about “radioactive shrimp” spread rapidly.

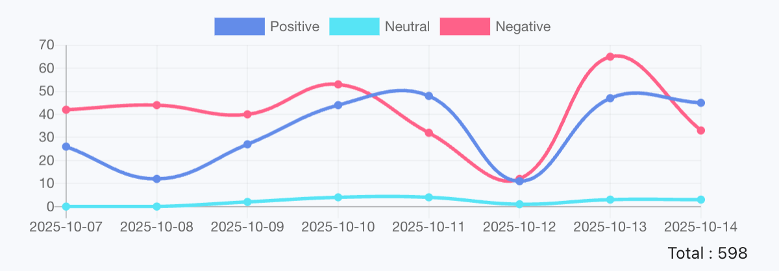

Data from Newstensity, a big-data media-monitoring platform, recorded 616 articles published between 7 – 14 October 2025. Coverage briefly dipped on 11–12 October, but surged again on 13 October, driven by new discoveries at the industrial site. Most reports centered on the ongoing investigation and the companies allegedly involved.

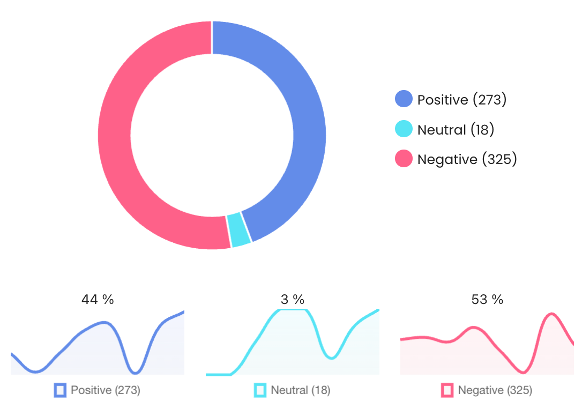

Sentiment analysis revealed that 53 percent (325 articles) were negative, emphasizing crisis and danger — including potential health impacts, environmental pollution, and risks to Indonesia’s export reputation. 44 percent (273 articles) carried positive framing, highlighting the government’s quick coordination among KLHK, BAPETEN, and the National Police’s criminal investigation unit (Bareskrim Polri), along with official reassurances that the contamination came from industrial metal, not ocean ecosystems or fish farms. Only 3 percent (18 articles) remained strictly neutral.

This contrast illustrated how mainstream media attempted to balance between fear and confidence: while the negative tone dominated early narratives, official responses gradually rebuilt some level of public assurance.

The highest intensity of coverage appeared in Jakarta (280 articles) — the country’s news epicenter — followed by South Sumatra (153) and East Java (127). Smaller but notable clusters appeared in Bali (20), Nusa Tenggara (12), Sulawesi (6), and Kalimantan–Papua (1–3).

This distribution shows how Indonesia’s information flow remains heavily centered in western regions, especially around Jakarta. Yet, the Cikande case also demonstrated how an environmental issue in a local industrial zone can quickly become a national concern when linked to export credibility and international scrutiny.

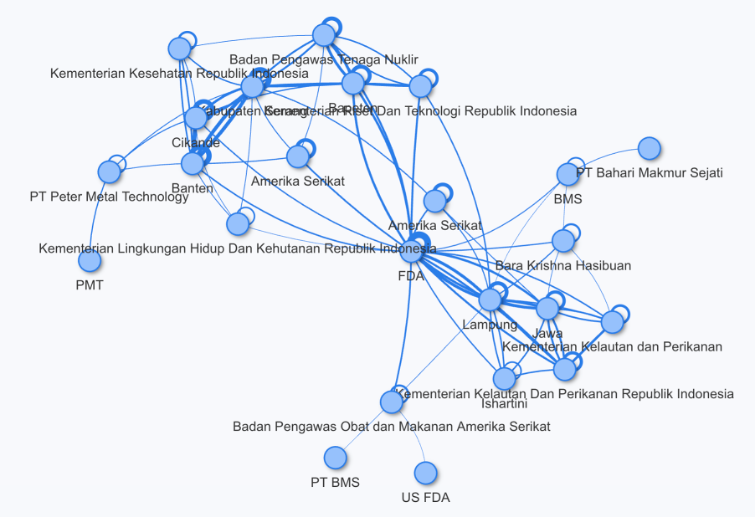

Network analysis revealed a tightly linked triad of key institutions: the FDA, KLHK, and BAPETEN.

Other agencies such as the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (KKP), and the Food and Drug Monitoring Agency (BPOM) emerged as supporting actors, ensuring inter-ministerial collaboration.

Mentions of the United States and Australia reflected the story’s global implications: this was no longer just a domestic environmental problem but also a trade and diplomatic issue affecting Indonesia’s export image abroad.

Overall, the media narrative painted the Cikande incident as a multi-sectoral crisis — intertwining food safety, environmental regulation, and international credibility.

The term #UdangRadioaktif (radioactive shrimp) trended nationwide after Reuters and AP reported the FDA findings. On X (formerly Twitter), public discussion exploded with hashtags #Cikande, #Cs137, and #KeamananPangan (food safety).

According to Socindex, between 7 – 14 October 2025, there were 1 163 posts by 498 unique users, reaching an audience of nearly 5.8 million people.

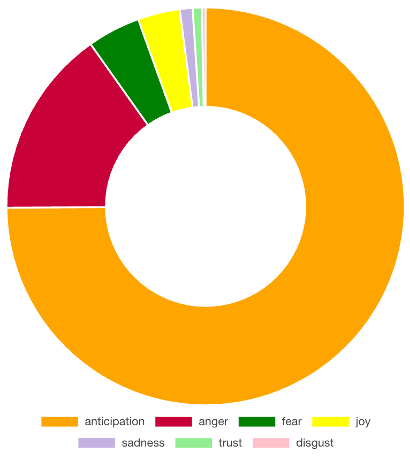

Emotions were dominated by fear, overshadowing anger or sadness. Many posts demanded clarity from KLHK, BAPETEN, BPOM, and KKP.

Interestingly, sentiment shifted on 10 October, when official government accounts — @Bapeten, @KemenLHK, @BPOM_RI, and @KKPgoid — began releasing transparent updates assuring the public that radiation levels were “within safe limits” and that the situation was under control. This proactive communication led to a brief surge of positive sentiment before skepticism returned days later.

Still, panic resurfaced when several outlets reported that Cs-137 levels were allegedly 857,000 times higher than the permissible limit — a number later clarified but never fully dismissed. Experts warned that such concentrations, if confirmed, could cause genetic damage, reproductive disorders, and long-term ecological collapse.

As coverage evolved, the conversation gradually shifted from fear to structural critique — focusing on weak environmental governance, industrial oversight failures, and hazardous-waste management in Cikande. Netizens began connecting the incident to broader pollution issues and Indonesia’s ongoing struggle with industrial waste disposal.

Bot-analysis showed that over 300 tweets came from organic human accounts, suggesting that the debate was largely authentic, not manipulated by automated campaigns.

For ordinary Indonesians, the “radioactive shrimp” story wasn’t just a headline — it hit close to home.

Behind every meme or joke online was a growing sense of unease: fishermen feared losing livelihoods; seafood traders reported falling sales; families started avoiding shrimp altogether.

While government agencies have worked to contain the situation, the deeper damage lies in eroding public trust — in food safety systems, in institutional competence, and in crisis transparency.

The crisis may have begun with shrimp, but its implications extend far beyond one product. It challenges the nation to confront how fragile its environmental governance truly is — and how silence can often be the most dangerous form of contamination.

Until the state can guarantee that our food and water are genuinely safe, fear will linger at every dinner table — a silent reminder of how the smallest particles can expose the biggest weaknesses.

The government’s decision to appoint personnel from the Nutrition Fulfillment Service Unit (SPPG) as Government Employees with Work Agreements (PPPK),…

The evolution of marketing over the past few years has shown a major shift, especially as digital marketing becomes the…

Freedom of opinion and expression is a constitutional right protected by law. Today, the public’s channel for voicing disappointment toward…

In January 2026, the internet was shaken by the viral spread of a book titled “Broken Strings: Fragments of a…

The government has begun outlining the direction of the 2026 State Budget (APBN 2026) amid ongoing global economic uncertainty. Finance…

The Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Communication, Information, and Digital Affairs (Komdigi), has officially temporarily blocked the use of…

A few years ago, electric cars still felt like a far-off future. They were seen as expensive, futuristic in design,…

Hydrometeorological disasters hit three provinces in Sumatra—Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra. Tropical Cyclone Senyar, spinning in the Malacca Strait,…

The heavy rainfall in late November 2025 caused flash floods that submerged parts of Aceh, West Sumatra, and North Sumatra….

When we consider people’s decisions today—what to buy, what issues to trust, and which trends to follow—one thing often triggers…