Sudewo Pati Regent Case Under Media Spotlight: Communication Analysis, Framing, and Public Perception

In recent times, public attention has again turned to leadership dynamics at the local level. Various cases involving regional heads—such…

The heavy rainfall in late November 2025 caused flash floods that submerged parts of Aceh, West Sumatra, and North Sumatra. In this tragedy, which claimed many lives, the Indonesian government’s disaster response received significant criticism. Instead of focusing on mitigation efforts, the framing of the narrative and normalization attempts were ramped up to calm public sentiment. This pattern is visible in various statements from political officials within President Prabowo Subianto’s “Red and White Cabinet.”

“Indeed, it seemed terrifying yesterday, right? There were various rumors on social media, we couldn’t meet, and so on. But when we got here, the media team was present at the location and there was no rain,” stated the Head of the National Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB), Lt. Gen. TNI Suharyanto.

This statement, however, failed to affirm the collective anxiety of the public and instead made them even angrier. The statement seemed to downplay the impact of the disaster that affected three provinces. On the same day the statement was made, Friday (November 28), BNPB reported that 174 people had died, 79 were missing, and 12 others were injured. The statement was in stark contrast to the available data, indicating that Suharyanto’s comment was more about framing the narrative than offering an empathetic response to the reality on the ground.

Michel Foucault, in his work Discipline and Punish (1975), redefined how modern power works. While Max Weber, in Politics as a Vocation (1919), emphasized the monopoly of violence as the backbone of the state’s legitimacy, Foucault argued that control over language, knowledge, institutions, and regulations plays a much more significant role. As a result, government power can permeate even the smallest aspects, such as the body (bio-politics).

In the context of disaster response, Foucault’s theory is highly relevant in interpreting the handling of the Sumatra floods. Almost a month after the floods struck, the call to declare the situation a national disaster had already resonated across the country. Some local governments had already expressed their inability to handle the floods. White flags, symbolizing “surrender,” had been raised in the affected areas.

However, the government again pushed the narrative of normalization. When asked about the status of the national disaster, President Prabowo stated that the situation was “under control” and that all resources had been “deployed.” The government’s reluctance to accept international aid was met with an arrogant response, asserting that Indonesia could handle the crisis.

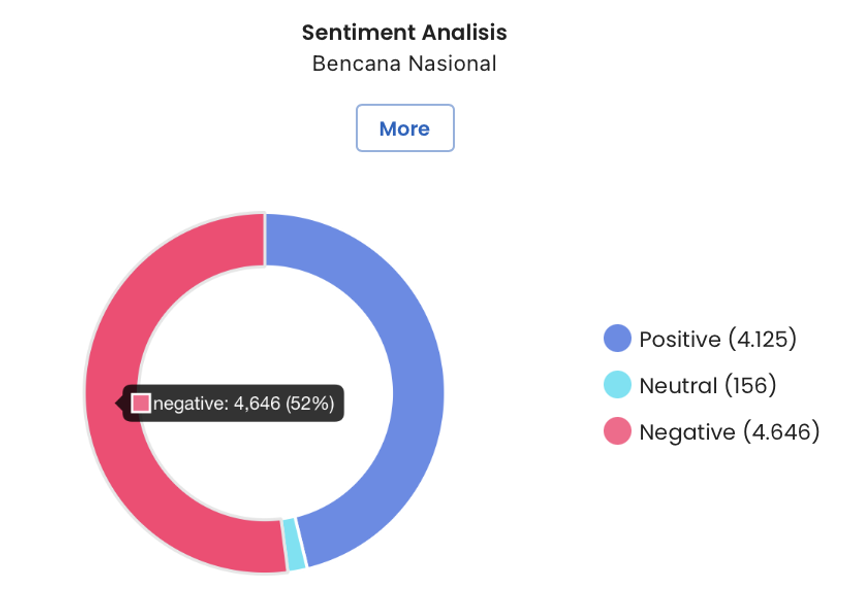

In fact, President Prabowo’s refusal to acknowledge the status of the floods as a national disaster, along with his emphasis on the government’s capability during the crisis, did not resonate positively. Using tools from Newstensity, it is apparent that news related to the Sumatra floods and its national disaster status was dominated by negative sentiment, indicating that the government’s crisis communication efforts were ineffective.

If we analyze further, the public statements from the government about the disaster response often revolve around a linguistic battle: debating “capable” vs. “incapable” and “under control” vs. “out of control.” Thus, the public’s anxiety and demands remain unmet by the government’s dismissive responses. In disaster management, the government’s role should be evaluated based on concrete actions and measurable results. As Foucault suggested, the government’s political decisions impact the “body” of its people. As of Wednesday (December 17), 1,059 people had been declared dead and 577,600 others were displaced. The growing number of victims is a direct result of the government’s decisions regarding disaster management.

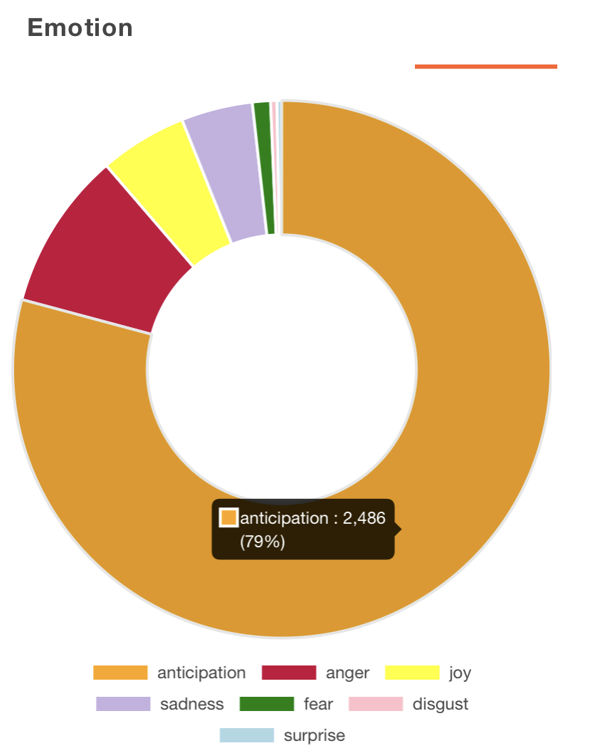

Analyzing conversations on social media between November 25 and December 17, 2025, using Socindex tools, it was revealed that emotions expressed on X (formerly Twitter) about the Sumatra floods were dominated by “anticipation,” followed by “anger.” The dominance of “anticipation” shows the government’s failure to provide reassurance during the crisis. This aligns with W. Timothy Coombs’ Situational Crisis Communication Theory (1999), which suggests that crisis communication narratives focused on denial (such as claiming that a crisis is “under control” or “beyond human power”) are often associated with attempts to protect those in power rather than addressing the victims.

Furthermore, a denial-based crisis communication approach also risks eroding public trust. Especially when what is promised contradicts the reality on the ground: the situation is said to be under control, but aid has not arrived. Unfortunately, this is the reality faced by flood victims, who complained that aid was delayed and that some refugees had begun setting up their own emergency posts. This initiative from the refugees further emphasizes how the government’s failure in crisis communication and disaster response has failed to reduce the public’s heightened sense of alertness.

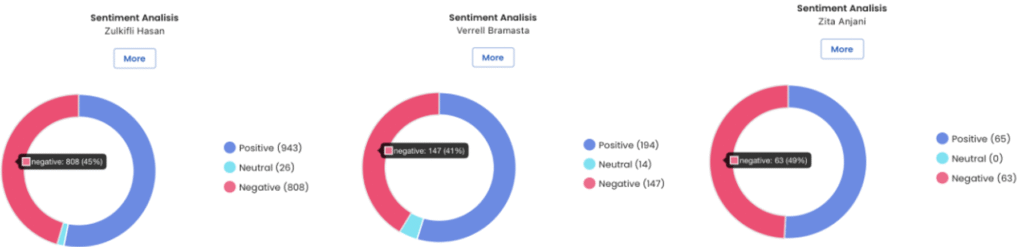

Not stopping at crisis communication, the failure of the government’s language politics was not just in verbal statements but also in the body language exhibited by several political figures when visiting disaster-affected areas. Figures such as Zulkifli Hasan (Zulhas), Verrell Bramasta, and Zita Anjani became the subject of public attention. Recently, their “actions” were caught on camera: Zulhas carrying a sack of rice, Verrell in his bulletproof vest, and Zita cleaning the mud.

However, the body language of these figures, which was supposed to reflect the presence of the country’s leaders, did not escape criticism and mockery. Many netizens commented on how Verrell’s protective gear seemed excessive, Zita’s sweeping style appeared “unnatural,” and Zulhas was accused of using the moment for image-building. Allegations of performativity from the public were impossible to ignore.

This can be seen in the media coverage of these figures in relation to the Sumatra floods. Using tools from Newstensity, a comparison of media coverage on the floods and these three political figures shows that almost half of the news coverage was negative. The surge of negative sentiment in national media reflects the dissatisfaction of netizens on social media. Symbolic gestures and political performativity, instead of drawing public sympathy, further deepened the emotional distance between the leaders and the people. Ironically, this same concern was also echoed by President Prabowo, who criticized political figures who were busy taking photos at the disaster site.

Ultimately, the Sumatra floods not only revealed the government’s failure in disaster response but also highlighted the questionable crisis communication. The government’s attempt to normalize and frame the narrative only exposed the government’s resignation and inability to address the disaster. The move to obscure the reality with the narrative of “the situation is under control” became evident when faced with the on-the-ground reality.

The controversy surrounding disaster management is about recognition. Recognition that the crisis has surpassed the capacity of local governments. Recognition that the state has not fully stepped in. Recognition that the hundreds of lives lost and the thousands who have lost their sense of security cannot be reduced to mere statistics.

The call for declaring a national disaster has echoed from various experts and non-governmental organizations. A public letter from Amnesty International Indonesia, referring to Law No. 11 of 2005 on the ratification of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), once again reminded the state’s obligation to mobilize all available resources, including international aid. The political decision to reject the national disaster status and close the door to foreign aid only further exposes what Foucault sought to reveal: that ultimately, our bodies, our lives, and deaths, are entirely under the control of the state. This is where the role of the state is tested. The policy decisions made in the future will serve as a measure of courage: the courage to admit failure, the courage to acknowledge suffering, and most importantly, the courage to stand by its most vulnerable citizens.

In recent times, public attention has again turned to leadership dynamics at the local level. Various cases involving regional heads—such…

A topic went viral on February 21, involving alumni of Indonesia’s Education Endowment Fund (LPDP). Dwi Sasetyaningtyas and her husband,…

Lately, the term SEAblings has been widely discussed across social media. The phenomenon gained traction after tensions between Southeast Asian…

Lieutenant Colonel Teddy Indra Wijaya, the Cabinet Secretary of the Republic of Indonesia, is currently carrying three major roles at…

The government’s decision to appoint personnel from the Nutrition Fulfillment Service Unit (SPPG) as Government Employees with Work Agreements (PPPK),…

The evolution of marketing over the past few years has shown a major shift, especially as digital marketing becomes the…

Freedom of opinion and expression is a constitutional right protected by law. Today, the public’s channel for voicing disappointment toward…

In January 2026, the internet was shaken by the viral spread of a book titled “Broken Strings: Fragments of a…

The government has begun outlining the direction of the 2026 State Budget (APBN 2026) amid ongoing global economic uncertainty. Finance…

The Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Communication, Information, and Digital Affairs (Komdigi), has officially temporarily blocked the use of…