Sudewo Pati Regent Case Under Media Spotlight: Communication Analysis, Framing, and Public Perception

In recent times, public attention has again turned to leadership dynamics at the local level. Various cases involving regional heads—such…

Every time a demonstration in Indonesia ends in chaos, the police almost always use the term “anarchistic” to explain the incident. The word appears repeatedly in press conferences, official releases, mainstream news and informal posts.

What does “anarchistic” actually mean? Is there an official definition in the law? Do the police have clear criteria? In reality, there are none. The word acts like rubber—burning tyres can be labelled anarchistic; refusing to disperse while sitting on the pavement can be too; even murals deemed unsightly may fall into the same category.

Yet in political theory, anarchism has a long history. Sheehan (2006) stresses that anarchism emphasises social order built from below, based on solidarity and free association, not chaos. Equating anarchism with “riots” is therefore a fundamental mistake.

Globally, similar misunderstandings persist. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2021) notes that since the 19th century western media have often portrayed anarchists as “mad bombers” or brutal figures who want to destroy social order. This narrative sticks even though historical research shows anarchism also played roles in anti‑colonial struggles, labour movements and attempts to build democracy.

We may recall history lessons: during the New Order, leftist literature—from communism to socialism—was banned. Those books were considered dangerous, as if they could corrupt minds in an instant, even though the state’s action was clearly political. For decades that fear was instilled.

The 1998 reforms were supposed to open a new path, yet the phobia never truly disappeared; it simply changed its face. On one hand, government leaders talk about democracy, openness and freedom of expression. On the other, authorities on the ground still act as before: suspecting books, discussions and people who think differently.

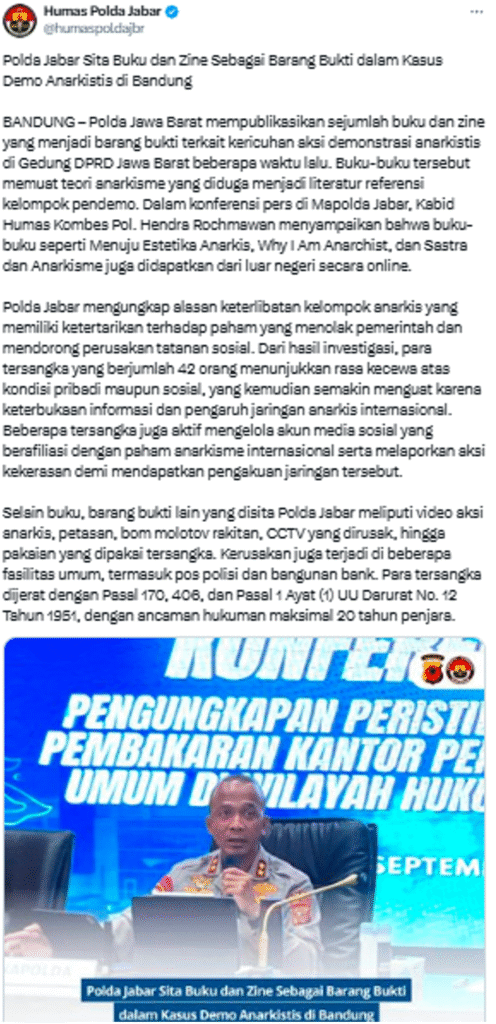

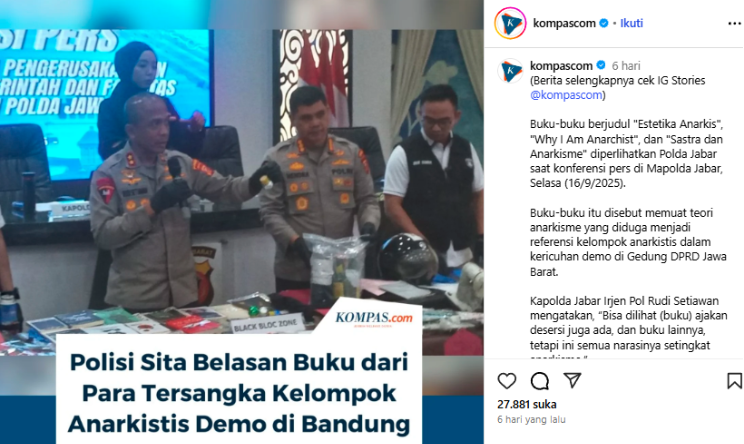

The latest case in September 2025 proves this. Police seized books from the home of a riot suspect, including works by Franz Magnis‑Suseno and Pramoedya Ananta Toer, and even referred to them as “criminal evidence.”

West Java Police Chief Rudi Setiawan said the books contained narratives “on the level of anarchism.”

Meanwhile, the Indonesian Government asserted that there is no ban on reading leftist or anarchist works.

This contradiction raises a big question: how does the state misunderstand anarchism, and how does that misunderstanding give rise to criminalising knowledge? If there is indeed no ban, why are books still confiscated?

World political history shows that anarchism is not synonymous with destruction. In Spain, anarchists played a major role in the 1936 Revolution, organising cooperatives to produce and distribute goods. In the Philippines, José Rizal’s ideas and the anti‑colonial reform movement were influenced by an anti‑authoritarian spirit close to anarchism.

In theory, Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin rejected state violence and proposed social solidarity as the basis of order. Emma Goldman, the American anarchist feminist, emphasised individual freedom and the struggle against gender oppression. All this demonstrates that anarchism is a complex tradition of thought, not merely a synonym for “rioting.”

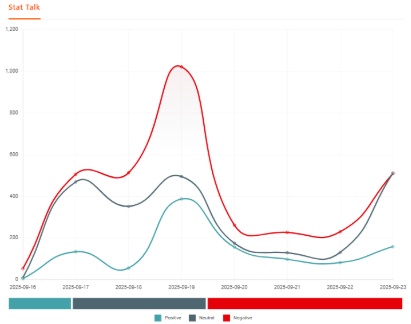

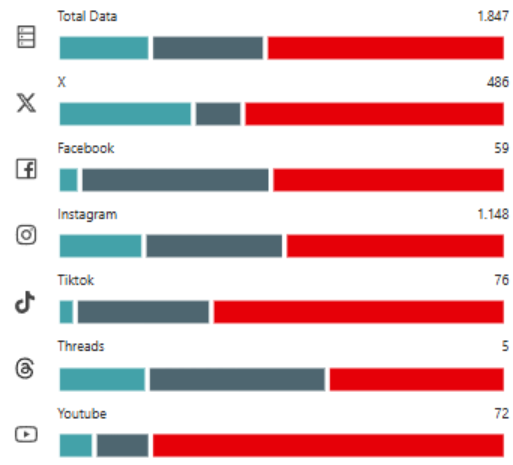

Data from Socindex, a big-data social media monitoring tool shows that every time the police mention “anarchistic/anarchism/anarchist” in a press conference, the term spikes on social media. For example, on 19 September 2025, a few days after the West Java Police held a press conference about riot suspects in Bandung and the seizure of books, there were 1 847 conversations and posts on social media about anarchism.

These posts were dominated by Instagram interactions, driven by media accounts reporting on the police’s claim that foreign funds had flowed to the suspects.

The phenomenon shows how quickly the authorities’ narrative becomes dominant on social media, revealing a strong relationship between state framing, mass media and public opinion.

Criminalising books and misusing the term “anarchism” seriously affects the quality of democracy. First, it limits the space for intellectual discussion: if reading philosophy can be considered criminal, campuses, libraries and discussion forums will operate under threat. Second, it creates symbolic repression—demonstrators accused of being anarchists immediately lose moral legitimacy before facts are verified. Third, it exposes policy contradictions: on the one hand the government wants to present a democratic face to the world; on the other, its apparatus practises repression.

The state’s misunderstanding of anarchism cannot be taken lightly. Using “anarchistic” as a catch‑all label is conceptually wrong and dangerous because it legitimises repression. Confiscating books unrelated to any crime further shows that the state remains afraid of knowledge. To defend democracy, the state must stop treating books and ideas as threats; openness to different thoughts is a basic condition of a healthy democracy.

Popular culture may see more clearly than political rhetoric. In the song Akhirnya Masuk Tipi, the band Majelis Lidah Berduri writes:

“Oh, Susi, teach them

How to spell,

The road is inscribed with scars,

The government cannot read them.”

The lyrics reflect this article’s central point: officials are busy labelling people “anarchists” and seizing books but fail to read the scars etched in the streets.

References:

Writer: Razhaq P.R. (Socindex), Ilustrator: Aan K. Riyadi

In recent times, public attention has again turned to leadership dynamics at the local level. Various cases involving regional heads—such…

A topic went viral on February 21, involving alumni of Indonesia’s Education Endowment Fund (LPDP). Dwi Sasetyaningtyas and her husband,…

Lately, the term SEAblings has been widely discussed across social media. The phenomenon gained traction after tensions between Southeast Asian…

Lieutenant Colonel Teddy Indra Wijaya, the Cabinet Secretary of the Republic of Indonesia, is currently carrying three major roles at…

The government’s decision to appoint personnel from the Nutrition Fulfillment Service Unit (SPPG) as Government Employees with Work Agreements (PPPK),…

The evolution of marketing over the past few years has shown a major shift, especially as digital marketing becomes the…

Freedom of opinion and expression is a constitutional right protected by law. Today, the public’s channel for voicing disappointment toward…

In January 2026, the internet was shaken by the viral spread of a book titled “Broken Strings: Fragments of a…

The government has begun outlining the direction of the 2026 State Budget (APBN 2026) amid ongoing global economic uncertainty. Finance…

The Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Communication, Information, and Digital Affairs (Komdigi), has officially temporarily blocked the use of…