Sudewo Pati Regent Case Under Media Spotlight: Communication Analysis, Framing, and Public Perception

In recent times, public attention has again turned to leadership dynamics at the local level. Various cases involving regional heads—such…

A few years ago, electric cars still felt like a far-off future. They were seen as expensive, futuristic in design, and suitable only for urban use. In 2025, Indonesia enters a pivotal year for the automotive industry. With the global economy slowing, consumption patterns shifting, and environmental awareness rising, one issue dominates the conversation: vehicle electrification.

This term no longer refers only to pure electric cars (Battery Electric Vehicles/BEVs). It now covers a broader range—hybrid, plug-in hybrid, and fully electric vehicles. In 2025, more people begin to feel that electrification is no longer distant—it is getting closer to everyday life.

The year 2025 is an interesting period to observe how Indonesia’s vehicle market is moving from conventional to electrified models. Market-leading manufacturers are increasingly active in launching electrified variants. New brands—especially from China—are also entering Indonesia and bringing electric vehicles as their main offering.

Even though electrification is still in an early phase, various data points indicate that electrified vehicles are growing far faster than conventional vehicles this year. According to the PwC eReadiness 2025 report, electric vehicle sales share in Indonesia reached around 18% of the total light vehicle market—an increase of 49% compared to the previous year, even as Indonesia’s overall automotive market declined. Another report noted that in Q1 2025, EV sales (including BEV, PHEV, and hybrid) surged 43.4% year-to-date, reaching 27,616 units sold.

However, calling this trend a “revolution” would be premature. What we are seeing is better described as a gradual transition—slow, uneven, and heavily influenced by region.

In general, Indonesia’s 2025 automotive market is still dominated by conventional vehicles. More than 80% of cars sold still rely on gasoline or diesel engines. The remainder is split between hybrids and pure EVs (BEVs). Even so, the growth rate of electrified models far outpaces conventional models. Hybrids are growing by double digits year-on-year, while BEVs grow even faster—though from a smaller base.

Hybrids are a particularly attractive segment. In practice, hybrids have become the main entry point for electrification. In Indonesia, this is not an accident. It reflects a pragmatic consumer mindset: open to new technology, but reluctant to take major risks.

For years, electric vehicles in Indonesia seemed to exist in two separate worlds. On one side, they were discussed as “the future”—clean energy, lower emissions, advanced technology. On the other side, EVs still felt out of reach for most people: expensive, limited options, mostly visible in big cities, and strongly associated with the upper middle class.

Then 2025 became a turning point. Perceptions began to shift. Vehicle electrification is no longer a niche topic—it is moving toward the center of the market.

Toyota—one of Indonesia’s automotive giants—did not limit its electrified offerings to premium segments. It started expanding into more affordable segments. One of the newest moves is the launch of the Toyota Veloz Hybrid in the Low MPV segment—Indonesia’s best-selling, most “family-oriented” car category.

This is not merely about a new product. It signals something bigger: when Toyota brings hybrid technology into the mass market, the message is clear—electrification is no longer only for a small group of people; it is becoming an option for many Indonesian families.

For most Indonesians, a car must meet practical requirements: usable daily, comfortable for the family, ready for long-distance trips, and not inconvenient. Throughout 2025, charging infrastructure has improved, but not evenly. Large cities such as Jakarta, Bandung, Surabaya, and Bali are relatively prepared. Outside Java, the number of public charging stations (SPKLU) is still limited and often concentrated in specific locations. This reality makes many potential buyers hesitate about BEVs.

Hybrids, in contrast, do not demand major behavior changes. There is no need to schedule charging times, and there is less anxiety about running out of power on intercity routes. Hybrids become the most logical alternative in a market where infrastructure is still incomplete.

Hybrids are widely seen as the best transitional bridge between conventional vehicles and fully electric vehicles for several reasons:

Through this approach, Toyota expects more consumers to move toward electrification gradually, with hybrids as a realistic and practical first step.

Toyota also understands that Indonesia is not a uniform market. Infrastructure is uneven, purchasing power varies, and mobility patterns differ widely. Therefore, Toyota does not force a single solution. The launch of Veloz Hybrid in the Low MPV segment is a strategic move. Low MPVs contribute nearly one-third of national vehicle sales. If electrification is to truly reshape the market landscape, this segment is the key.

Veloz Hybrid does not attempt to look like a “future gadget.” Instead, it presents itself as a family car that is more efficient, quieter, and more effective in daily life.

Toyota has long experience in reading Indonesia’s market. Its dominance was built not only through product strength but also through deep understanding of consumer behavior across regions. Therefore, Toyota’s electrification strategy should be seen as an industry signal, not merely an internal business decision.

Toyota Veloz Hybrid is not positioned as a flashy symbol of the future. It does not rely on futuristic design or dramatic “technology disruption” narratives. Instead, it feels familiar—like a family vehicle with more efficient technology. This approach matters. Many Indonesian consumers still see new technology with a mix of curiosity and caution. Veloz Hybrid does not challenge tradition head-on—it blends into it.

With a price difference that is not far from the conventional version, Veloz Hybrid offers a simple proposition: more savings in the long term, without major changes in everyday use.

The Hybrid EV Lintas Nusa event can also be interpreted as Toyota’s attempt to address public skepticism through real actions, not just promotional brochures. By driving hybrid vehicles across regions, Toyota tries to prove that this technology is not only for big cities or limited use cases. For Indonesian consumers, direct experience often carries more weight than technical claims. Once hybrids prove capable of long-distance travel without problems, many concerns tend to fade.

Hybrids allow Toyota to delay large-scale investment in fully electric vehicles, while still appearing modern. Launching Veloz Hybrid in the Low MPV category is not just an idea—it is a carefully structured business strategy. Toyota participates in electrification as far as market conditions and regulations allow. Hybrid EV Lintas Nusa serves as evidence that hybrids fit Indonesia’s context.

But behind that narrative is another message: hybrids do not require systemic change. They can travel long distances without charging stations. They do not demand major changes in energy policy. They support the idea that “change can happen without disrupting the existing structure.” In this sense, hybrids are not just technology—they are a tool to normalize a slow transition.

Over the past few years, the Indonesian government has positioned itself as an important player in the global EV ecosystem. Narratives about nickel downstreaming, battery industry development, and net-zero targets are frequently repeated. In policy documents, BEVs are often framed as the final destination. Yet at the implementation level, policy direction does not appear fully decisive. Incentives exist, but are not always consistent. Infrastructure is built, but unevenly. Targets are set, but without a clear social roadmap: who will shift, when, and at whose cost. As a result, the market fills the leadership vacuum.

Hybrids grow not because the state explicitly promotes them as the ideal transition solution, but because they are the most compatible with the market’s current realities. The state tends to follow, not lead.

In electrification discourse, the government often appears in the background: tax incentives, industrial roadmaps, emissions targets. But on the ground, the direction of change is shaped more by market logic and corporate strategy.

In the absence of strong policy leadership, automotive corporations move based on their own logic: minimize risk and maximize market acceptance. This is where hybrids become “ideal”—not because they are the greenest, but because they are the safest. For a large corporation like Toyota, hybrids are a compromise technology that lets the brand look progressive without betting too much capital and reputation.

Toyota is often praised for its multi-pathway electrification strategy. In Indonesia, that approach can also be read as a response to policy uncertainty. By not committing fully to BEVs, Toyota:

Hybrids become Toyota’s way to stay dominant without waiting for the state to be fully ready. In this relationship, the corporation can appear more agile than the state. Hybrid EV Lintas Nusa showcases hybrids as tough and suitable for Indonesia. But underneath, there is another narrative: the transition can happen without systemic change. Instead of pressuring the state to accelerate SPKLU rollout and energy reform, hybrids can reduce that urgency in public perception.

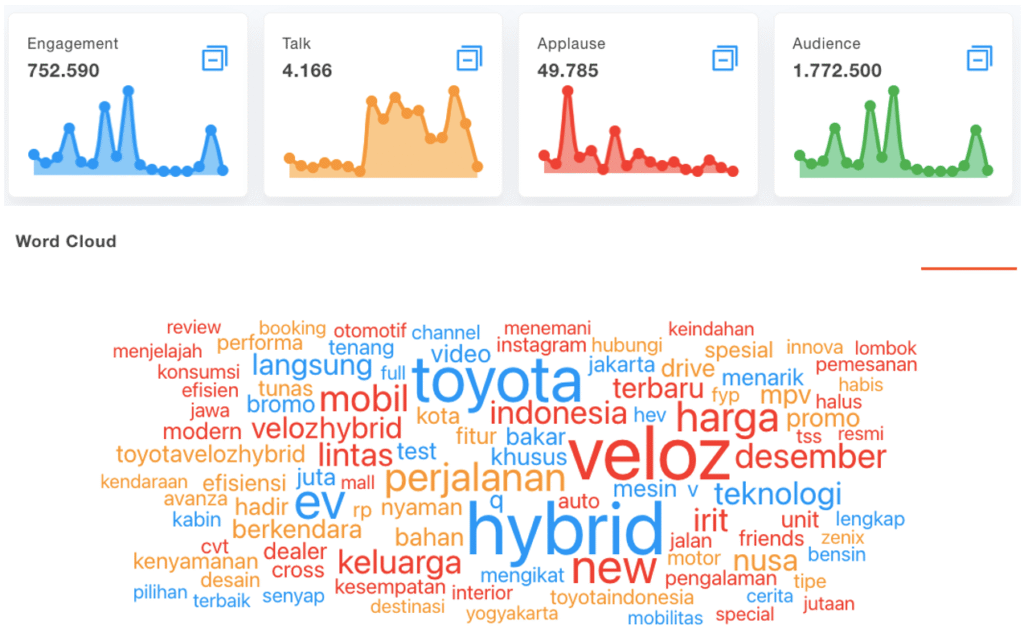

In the last two weeks, social media discussion has noticeably increased. There is a wave of test-drive content, unboxing videos, and media coverage praising fuel efficiency, cabin comfort, and the touring capability of Veloz Hybrid (for example, reviews and reels by automotive media).

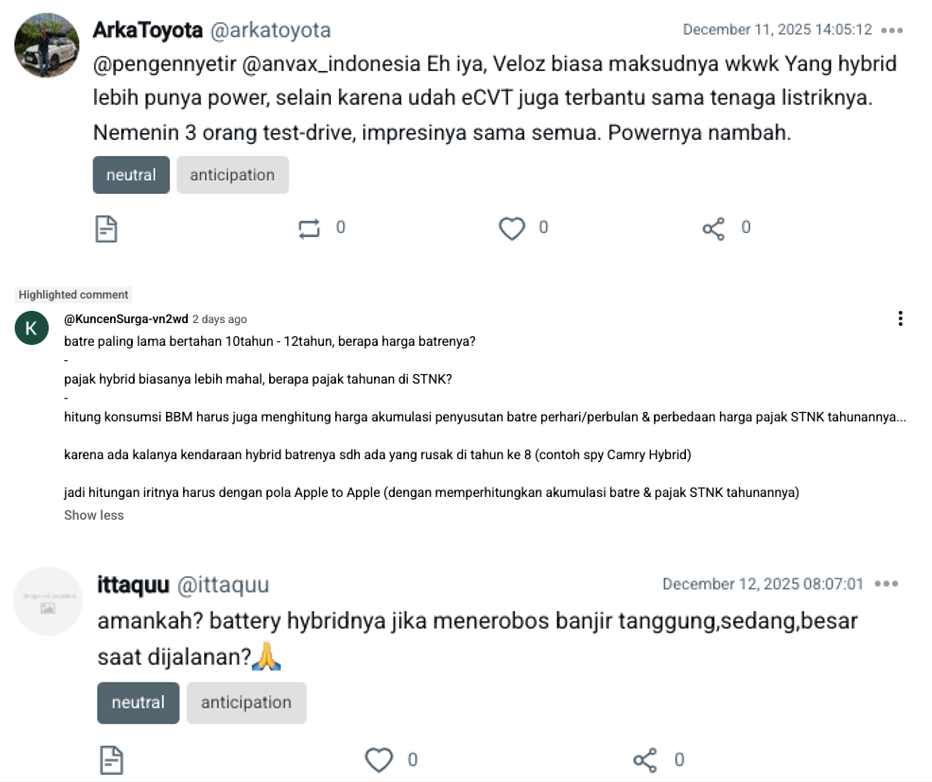

Netizen reactions are mixed: many praise efficiency and competitive pricing, while others raise questions and doubts about long-term maintenance costs, service and spare-part availability, and infrastructure readiness if users later want to switch fully to BEVs. Test drive posts and Lintas Nusa coverage were published as reels and videos from last week up to yesterday—showing public attention remains high and the discussion is active.

Conversation about Veloz Hybrid and vehicle electrification has risen sharply. The discussion pattern is relatively consistent: positive, skeptical, and conceptually confused. These three patterns suggest that the public accepts hybrids as a fair compromise, EV adoption remains rational rather than emotional, and electrification literacy is still limited. This also shows that people do not automatically buy “green narratives.” Many still see cars primarily as an economic decision, not a moral one.

Social media discussion also indicates that the public views electrification as an individual choice, not a collective project. People talk about price, savings, and service costs—not national emissions or energy independence. This is not solely the public’s “fault.” When the state does not lead the transition narrative as a shared project, it is natural for citizens to position themselves as rational consumers, not agents of change.

Indonesia’s automotive industry in 2025 shows a clear direction toward electrification, reflected in strong growth in EV and hybrid markets—even though total national sales are still dominated by conventional vehicles. The launch of Toyota Veloz Hybrid and the Hybrid EV Lintas Nusa event mark a new stage of electrification in Indonesia: more practical, more relevant, and more widespread.

If electrified vehicles once felt like a distant future, 2025 shows that the future is being built gradually—through rational compromises. Indonesia’s car usage map will shift, but not through extreme leaps. It will change through familiar pathways: family cars, reasonable pricing, and technology that does not force behavior changes.

In that context, hybrids are not just a transitional technology. They are the language of transition between old habits and Indonesia’s electrified future. Toyota Veloz Hybrid suggests electrification is moving forward—but very cautiously. It is safe for the industry, safe for middle-class consumers, and relatively safe for a state that is not yet ready to take major risks.

Perhaps that is the key to Indonesia’s electrification success: not forcing the future to arrive faster, but inviting society to walk toward it together.

In recent times, public attention has again turned to leadership dynamics at the local level. Various cases involving regional heads—such…

A topic went viral on February 21, involving alumni of Indonesia’s Education Endowment Fund (LPDP). Dwi Sasetyaningtyas and her husband,…

Lately, the term SEAblings has been widely discussed across social media. The phenomenon gained traction after tensions between Southeast Asian…

Lieutenant Colonel Teddy Indra Wijaya, the Cabinet Secretary of the Republic of Indonesia, is currently carrying three major roles at…

The government’s decision to appoint personnel from the Nutrition Fulfillment Service Unit (SPPG) as Government Employees with Work Agreements (PPPK),…

The evolution of marketing over the past few years has shown a major shift, especially as digital marketing becomes the…

Freedom of opinion and expression is a constitutional right protected by law. Today, the public’s channel for voicing disappointment toward…

In January 2026, the internet was shaken by the viral spread of a book titled “Broken Strings: Fragments of a…

The government has begun outlining the direction of the 2026 State Budget (APBN 2026) amid ongoing global economic uncertainty. Finance…

The Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Communication, Information, and Digital Affairs (Komdigi), has officially temporarily blocked the use of…