Sudewo Pati Regent Case Under Media Spotlight: Communication Analysis, Framing, and Public Perception

In recent times, public attention has again turned to leadership dynamics at the local level. Various cases involving regional heads—such…

Hydrometeorological disasters hit three provinces in Sumatra—Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra. Tropical Cyclone Senyar, spinning in the Malacca Strait, is suspected of triggering extreme rainfall from 25–27 November 2025 across the area. Flash floods and landslides occurred massively in all three regions. Worse, rampant deforestation across Sumatra further aggravated conditions. Logs from systematic logging were swept away by floodwaters, intensifying the damage.

Media attention quickly turned to Sumatra. The disaster became a headline that drew public sympathy. Without delay, concerned citizens extended help to support recovery efforts.

Unfortunately, the government displayed a failure in managing this disaster. A lack of anticipation, slow response, and insensitive statements by officials worsened conditions on the ground. Instead of acting as a calming force during a crisis, the government failed to build factual and empathetic communication. This not only hindered recovery, but also eroded public trust in the state.

To understand how the government’s reputation collapsed in a systematic way, this article examines several controversial policies and official statements that—ironically—embarrassed the institutions they represent.

Preliminary data from Indonesia’s National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB) dated 18 December 2025 recorded 1,059 deaths, 192 people still missing, and up to 7,000 injured. Impacted areas reached 52 regencies/cities. The disaster forced 105,992 people to evacuate. Damage to facilities and infrastructure included 147,236 damaged houses, around 1,600 public facilities, 219 health facilities, 67 education facilities, 434 places of worship, 290 buildings/offices, and 145 damaged bridges.

In other words, the Sumatra disaster caused extensive destruction, loss of life, and socio-economic harm. This fueled public pressure to declare it a national disaster.

Even so, a disaster affecting three provinces has not been formally designated as a national disaster. On 3 December 2025, President Prabowo—through Coordinating Minister for Human Development and Culture (Menko PMK) Pratikno—instructed that the Sumatra disaster be treated as a national priority, including guarantees that national funds and logistics would be fully available.

Prabowo appeared aware of demands for a national disaster declaration. During a Cabinet Plenary Session on Monday, 15 December 2025, he responded to those aspirations.

“Some people are shouting that this should be declared a national disaster. We’ve deployed [resources]; this is three provinces out of 38. So the situation is under control. I keep monitoring it,” Prabowo said, as quoted by Kompas.com. He promised to form a task force for rehabilitation and reconstruction.

The government’s approach—treating the response as a national priority while refusing to officially declare a national disaster—looks ambiguous. On one hand, the government claims full commitment to recovery; on the other, it avoids symbolic recognition of the disaster’s scale and severity. Prabowo’s emphasis that the situation is “under control” strengthened perceptions that the government prioritizes an image of stability over public empathy. It creates an impression of denial toward the disaster’s urgency.

Coordinating Minister for Food Affairs Zulkifli Hasan visited the disaster area on 30 November 2025, going to Koto Panjang, Ikur Koto, Koto Tangah, Padang (West Sumatra). He uploaded a video showing himself carrying a sack of rice aid and helping clean mud from residents’ homes.

A similar move was made by his daughter, Zita Anjani, the President’s Special Envoy for Tourism. She posted a video of herself visiting disaster victims and cleaning muddy floors in flood-hit homes.

Instead of gaining sympathy, these actions triggered criticism from netizens who saw the Sumatra disaster being used as a stage for image-building. The public viewed symbolic gestures without concrete policy as reinforcing the impression that officials were more focused on optics than accelerating recovery.

Carrying rice or cleaning mud can indeed signal empathy. However, the absence of concrete policies that speed up post-disaster recovery made Zulhas and Zita’s actions appear performative. The public wants a systematic and coordinated state presence—not officials chasing camera moments.

Kompas Research and Development (Litbang Kompas) released public opinion polling on the central and local governments’ responses in Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra. In a telephone survey conducted 8–11 December 2025 with 510 respondents across 38 provinces, 56.4% believed the central government had a strong commitment to making the Sumatra disaster response a national priority. Yet 47.3% said the government response was slow. This suggests the public recognizes stated commitment, but sees weak execution.

Public doubts were reflected in field realities. An early warning from BMKG (Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysics Agency) about the potential of Tropical Cyclone Senyar—eight days before the disaster—did not receive government follow-up.

The fact that logs were swept away by flash floods exposed the long-ignored problem of massive deforestation in Sumatra. This was not purely a natural event, but an accumulation of environmental damage from uncontrolled logging—showing state failure in managing ecological risk.

Disaster handling in Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra also faced access constraints. BNPB stated that as of 14 December 2025, 19 sub-districts and hundreds of villages across the three provinces remained difficult to reach. Limited access became a serious barrier to aid distribution and victim response.

Prabowo’s statement rejecting assistance from other countries, along with Social Affairs Minister Saifullah Yusuf’s statement requiring citizen aid to obtain government permission, created additional controversy. These statements gave the impression that the government prioritized ego and bureaucracy over emergency response in Sumatra.

This sequence shows failure to build a preparedness-and-empathy narrative even before the disaster. Ignoring BMKG’s early warning undermined credibility as a data-driven, responsive actor. The deep-rooted deforestation problem revealed the state’s negligence in protecting nature—effectively planting a time bomb for ecological catastrophe. When disaster struck, the public saw slow mitigation and response.

The situation worsened due to insensitive official messaging—such as refusing international aid and placing citizen help behind bureaucracy. Such messages can be seen as unempathetic and dismissive of the real emergency. Instead of strengthening trust, they triggered public antipathy.

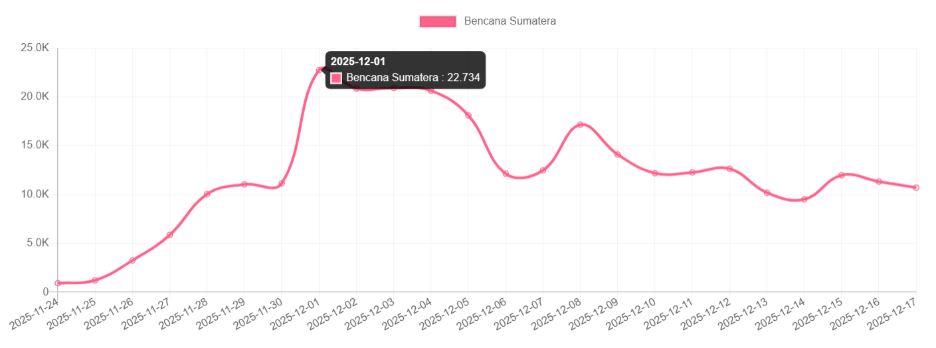

Media monitoring used keyword combinations of “disaster,” “flood,” “Sumatra,” and “Aceh” from 24 November to 17 December 2025. The results recorded 293,284 news items related to the Sumatra disaster during the period. Coverage peaked on 1 December 2025 with 22,734 articles, triggered by President Prabowo’s visit to the affected areas. Of the total, 154,047 articles included the keyword “government.”

This suggests the government had a major opportunity to shape a positive image by performing strong disaster management. Instead, the large volume of coverage spotlighting the government failed to build strong positive perception. High attention turned into criticism—driven by unsatisfactory performance and unnecessary behaviors from officials.

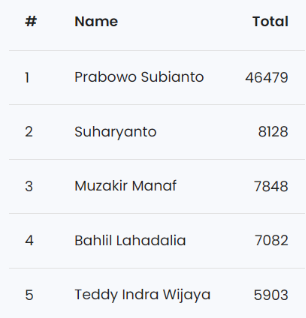

The list of top persons was dominated by President Prabowo, appearing in 46,479 articles—reflecting his central role as head of state and key decision-maker. Below him, BNPB Chief Suharyanto appeared in 8,128 articles as the head of the main technical institution for disaster response.

Aceh Governor Muzakir Manaf ranked third with 7,848 mentions, showing strong media focus on regional leadership. Next were Energy and Mineral Resources Minister Bahlil Lahadalia (7,082) and Cabinet Secretary Teddy Indra Wijaya (5,903).

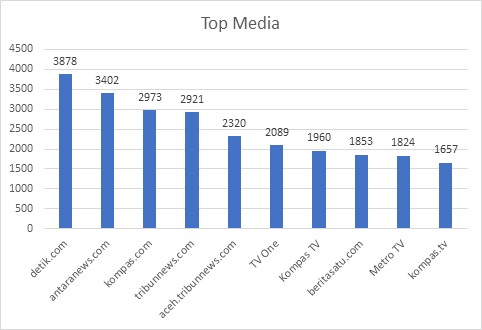

The top 10 outlets were dominated by online media: detik.com led with 3,878 articles, followed by antaranews.com (3,402) and kompas.com (2,973). Tribunnews.com ranked fourth (2,921), followed by aceh.tribunnews.com (2,320) representing local coverage in impacted areas. TV channels also appeared—TV One (2,089) and Kompas TV (1,960). The list continued with beritasatu.com (1,853), Metro TV (1,824), and kompas.tv (1,657).

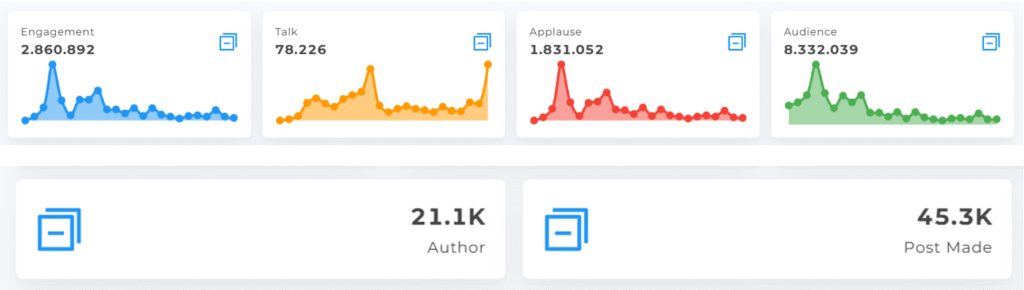

Conversation on X during the period was broad: 21.1 thousand authors generated 45.3 thousand posts. Engagement was extremely high: 2,860,892 total engagement, with talk 78,226, applause 1,831,052, and potential audience reach up to 8,332,039 accounts.

This indicates the Sumatra disaster became a major topic on social media. High engagement reflected netizens’ emotional response to the humanitarian impact—and the government’s role in handling it.

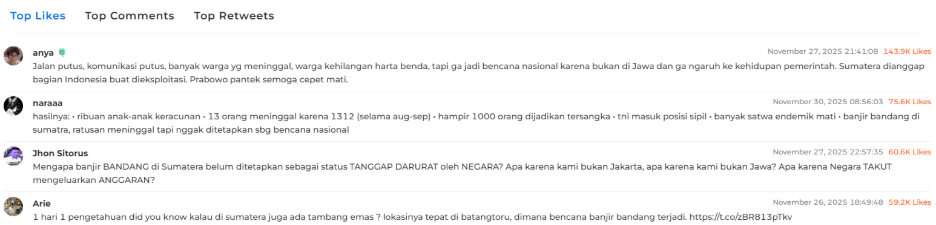

Consistent with high conversation, the top liked tweets showed that the strongest public reaction was anger and disappointment at perceived state incompetence.

The most liked tweet (by anya) strongly criticized unequal treatment when disasters happen outside Java—especially the refusal to declare a national disaster. Other highly liked posts (including from naraaa and Jhon Sitorus) also highlighted the absence of national emergency status.

This pattern clearly shows that netizens’ emotions and attention focused more on perceived government failure—slow, unfair, and indecisive—rather than appreciation for response measures. As a result, the conversation on X grew into sharp criticism of the government, not praise.

In the context of the Sumatra disaster, it must be admitted the government has entered a public relations disaster. The government failed not only in technical disaster management, but also in reading public sentiment. To get out of this crisis, the government needs fundamental change in thinking, action, and communication.

First, the government must openly and honestly acknowledge that the impact is massive. Saying the situation is “under control” amid high fatalities, non-functioning public facilities, and devastated livelihoods looks like denial and downplaying. The government must understand that recognition is the first step to rebuild trust.

Second, the government must realize symbolic steps also matter to mobilize public support—especially regarding the demand for a national disaster declaration. The lack of formal status makes the public see denial and injustice. A national disaster status can act as a strong alarm that the state is deploying all resources to focus on Sumatra and reduce suffering.

Third, the government must discipline public officials’ behavior. Visits combined with performative acts will only deepen negative sentiment. The government needs one unified voice and stance, and must suppress personal showmanship by officials seeking sympathy. Communication should be centralized to manage public messages and prevent confusion.

The government must change its mindset in managing its image. Narratives of stability that contradict ground realities must be abandoned. The government should focus on restoring public trust overall—requiring extra effort because it is tied to government performance across all levels.

At minimum, the government must acknowledge the disaster’s impact, handle response accountably, and maintain consistency between statements, actions, and conditions on the ground. Without this shift, the Sumatra disaster will be remembered not only as a natural tragedy, but also as a symbol of state failure—even in something as basic as empathy.

In recent times, public attention has again turned to leadership dynamics at the local level. Various cases involving regional heads—such…

A topic went viral on February 21, involving alumni of Indonesia’s Education Endowment Fund (LPDP). Dwi Sasetyaningtyas and her husband,…

Lately, the term SEAblings has been widely discussed across social media. The phenomenon gained traction after tensions between Southeast Asian…

Lieutenant Colonel Teddy Indra Wijaya, the Cabinet Secretary of the Republic of Indonesia, is currently carrying three major roles at…

The government’s decision to appoint personnel from the Nutrition Fulfillment Service Unit (SPPG) as Government Employees with Work Agreements (PPPK),…

The evolution of marketing over the past few years has shown a major shift, especially as digital marketing becomes the…

Freedom of opinion and expression is a constitutional right protected by law. Today, the public’s channel for voicing disappointment toward…

In January 2026, the internet was shaken by the viral spread of a book titled “Broken Strings: Fragments of a…

The government has begun outlining the direction of the 2026 State Budget (APBN 2026) amid ongoing global economic uncertainty. Finance…

The Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Communication, Information, and Digital Affairs (Komdigi), has officially temporarily blocked the use of…