From SPPG to PPPK: The Dynamics of Program-Based Staffing in Indonesia’s Civil Service Reform

The government’s decision to appoint personnel from the Nutrition Fulfillment Service Unit (SPPG) as Government Employees with Work Agreements (PPPK),…

Finance Minister Purbaya Yudhi Sadewa underscored the government’s uncompromising stance against illegal used-clothing imports, which he stated have harmed the state. He reiterated that he would not hesitate to take action against any parties resisting or opposing the crackdown.

According to Purbaya, resistance indirectly indicates acknowledgment of wrongdoing. He argued that thrifting involving illegal imported goods has disrupted state revenue and violated existing regulations. Illegal imports, he added, have made the domestic market unhealthy and suppressed the national garment industry.

To strengthen enforcement, the government is preparing a special regulation in the form of a Minister of Finance Regulation (PMK) that will provide a stronger legal basis for imposing sanctions. Purbaya said violators would face a range of penalties—from destruction of goods, fines, imprisonment, to prohibitions on engaging in import activities.

Illegal used-clothing imports involve an organized network comprising importers and complicit officials along distribution routes. Findings from the Ministry of Trade—specifically 19,391 bales worth Rp112.3 billion stored in 11 warehouses in West Java—indicate that the operation is large and systematic.

These goods enter not only through official ports but also via trucks, hidden warehouses, and land routes across multiple provinces. Generally, illegal used clothing enters through two main corridors:

There are indications of bribery within the business. For a single container of used clothing, illegal importers reportedly pay around Rp550 million to certain officials to pass inspections. More than 100 containers are estimated to enter illegally each month, causing potential state losses reaching hundreds of billions of rupiah. The scale suggests involvement from individuals with authority and access.

The issue is exacerbated by weak surveillance. Indonesia’s vast territory with thousands of islands far exceeds the capacity of the limited maritime patrol fleet, making complete eradication of smuggling nearly impossible. This situation enables rogue importers to exploit loopholes.

The ban on used-clothing imports exists to protect the domestic textile industry. Imported used clothing is typically sold at low prices, distorting market prices and encouraging consumers to shift away from locally produced goods.

Furthermore, imported used clothing poses health risks. Without sanitation guarantees, such items may carry bacteria, fungi, viruses, or hazardous chemical residues from their country of origin—potentially causing skin diseases or infections.

Used-clothing imports are prohibited under Minister of Trade Regulation No. 40/2022, which revises Regulation No. 18/2021 on prohibited import–export goods. In this regulation, used clothing and other secondhand items fall under HS code 6309.00.00 and are classified as prohibited imports.

Several legal provisions can be used against illegal importers:

The government also oversees e-commerce through:

Sellers or platforms promoting used-clothing imports must ensure their content complies with the law. Violations of Article 18 of Regulation No. 50/2020 may result in administrative sanctions ranging from written warnings to business license revocation.

Data from BPS cited by tempo.co shows fluctuating import volumes between 2021 and 2025:

A sharp spike occurred in 2024, reaching 3,865.40 tons. From January to August 2025, imports dropped to 1,242.8 tons, significantly lower than in 2024 but still far above levels observed in 2021–2023.

Why does BPS still record import data despite the ban? According to Ni Made Kusuma Dewi, Head of Public Relations at the Ministry of Trade, the recorded imports represent legal exceptions, such as:

Between 2024 and 2025, the Directorate General of Customs and Excise (DJBC) handled 2,584 cases of used-clothing smuggling worth Rp49.44 billion. Several high-value enforcement cases occurred in 2025:

These examples represent only a fraction of the enforcement actions undertaken.

Minister Purbaya reiterated his refusal to engage in dialogue with thrifting proponents, asserting that imported used clothes remain illegal regardless of context. He stressed that the ban is not about potential tax revenue but about compliance with customs law.

He also rejected the idea of legalizing thrifting, even if sellers were willing to pay taxes. The government, he said, will not seek revenue from activities that clearly violate regulations. The priority is to stop the flow of illegal goods and cleanse the domestic market of prohibited products.

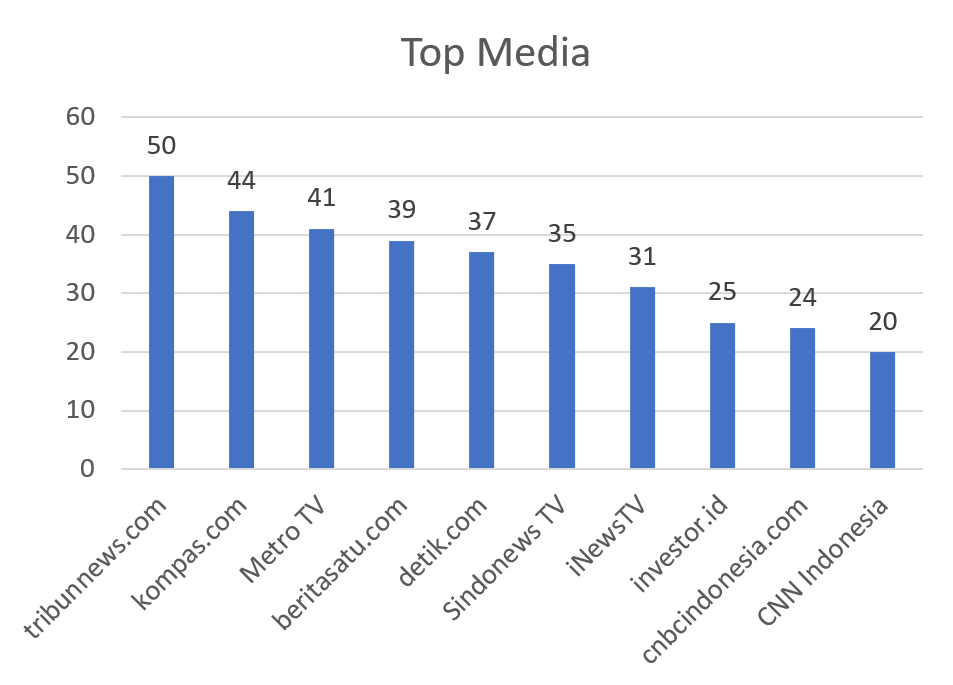

Media coverage fluctuated throughout 1–27 November 2025, with peaks indicating renewed public attention. A significant spike occurred on 20–21 November, reaching 464 articles. This surge was driven by Purbaya’s firm stance against engaging with thrifting communities and supporters of used-clothing imports. Total media coverage during this period reached 3,423 articles.

Online media dominated coverage:

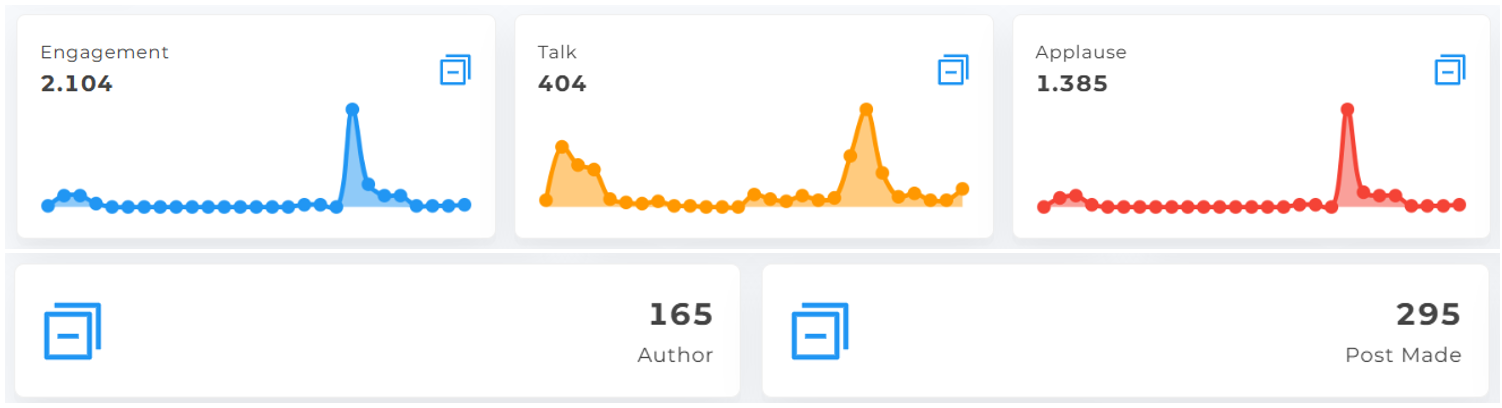

On X, the issue did not spark major public discourse. From 295 posts by 165 accounts, total engagement reached 2,104, predominantly from 1,385 likes. This indicates that the topic did not generate strong emotional engagement or widespread debate.

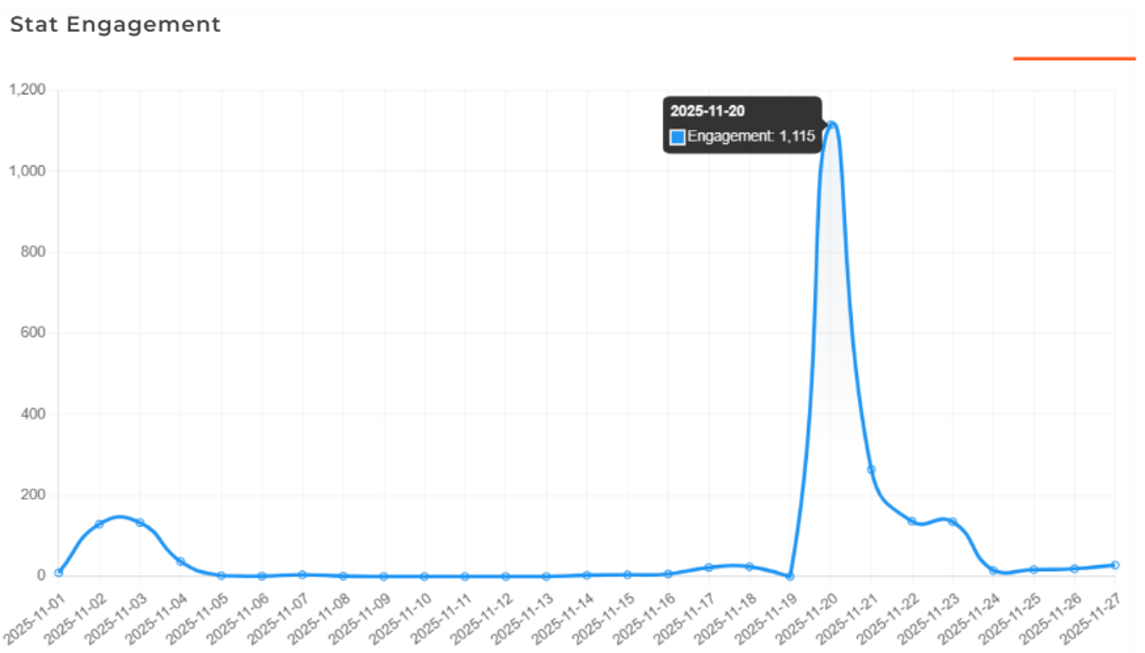

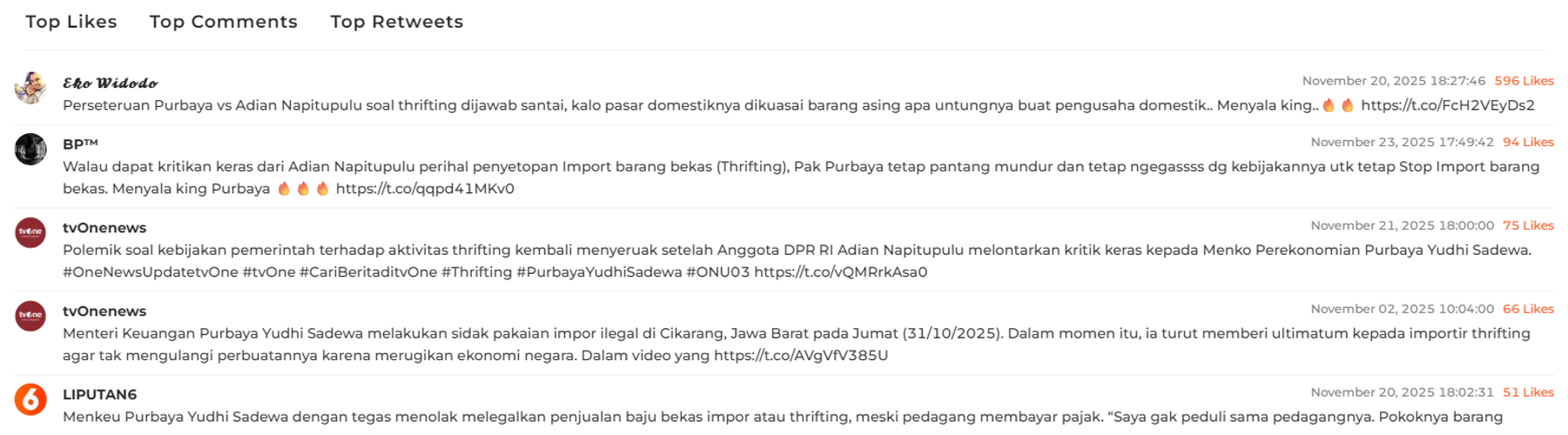

Engagement remained low throughout early to mid-November, with several days recording zero interactions. The only major spike—over 1,100 interactions on 20 November—correlated with a viral post featuring Purbaya’s firm statement. Engagement quickly fell back afterward.

The most-liked post came from user @ekowboy2, who shared a video clip of Purbaya’s statement emphasizing his support for domestic industry.

Posts highlighting contrasting statements between Purbaya and legislator Adian Napitupulu also drew significant attention—indicating that online engagement increases when policy debates intersect with political conflict.

Minister Purbaya’s firm stance in banning illegal used-clothing imports reflects the government’s commitment to protecting domestic markets and upholding customs law. Enforcement actions and upcoming regulatory reinforcements signal serious intent to end smuggling networks.

Nonetheless, major challenges remain. Indonesia’s vast geography, complex smuggling routes, and systemic loopholes demand consistent, coordinated, and long-term action. Only with sustained efforts can the government successfully cut off illegal import channels and ensure a healthier domestic market.

The government’s decision to appoint personnel from the Nutrition Fulfillment Service Unit (SPPG) as Government Employees with Work Agreements (PPPK),…

The evolution of marketing over the past few years has shown a major shift, especially as digital marketing becomes the…

Freedom of opinion and expression is a constitutional right protected by law. Today, the public’s channel for voicing disappointment toward…

In January 2026, the internet was shaken by the viral spread of a book titled “Broken Strings: Fragments of a…

The government has begun outlining the direction of the 2026 State Budget (APBN 2026) amid ongoing global economic uncertainty. Finance…

The Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Communication, Information, and Digital Affairs (Komdigi), has officially temporarily blocked the use of…

A few years ago, electric cars still felt like a far-off future. They were seen as expensive, futuristic in design,…

Hydrometeorological disasters hit three provinces in Sumatra—Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra. Tropical Cyclone Senyar, spinning in the Malacca Strait,…

The heavy rainfall in late November 2025 caused flash floods that submerged parts of Aceh, West Sumatra, and North Sumatra….

When we consider people’s decisions today—what to buy, what issues to trust, and which trends to follow—one thing often triggers…