Teddy Indra Wijaya Pursues Seskoad and an ITB PhD: Between Capacity Building and Shifting Public Perception

Lieutenant Colonel Teddy Indra Wijaya, the Cabinet Secretary of the Republic of Indonesia, is currently carrying three major roles at…

Lately, the term SEAblings has been widely discussed across social media. The phenomenon gained traction after tensions between Southeast Asian netizens and South Korean netizens (KNetz) erupted on X. Many people were surprised by how coordinated netizens appeared—from Jakarta to Bangkok to Manila. In everyday online life, Southeast Asian countries often clash in “digital civil wars,” ranging from cultural debates to football rivalries. Yet racist sentiment and condescending attitudes from outside the region seemed to act as a catalyst, pulling them together.

A long-suppressed sense of shared fate surfaced. Southeast Asian communities are frequently caught in biased global stereotypes—ranging from poverty stigma to discriminatory beauty standards. Although the region shares cultural and historical ties, national identity typically outweighs regional identity. That is why cross-border solidarity felt notable: insults from outside were increasingly perceived as an attack on the entire region, not just one country.

As reported by Media Indonesia, the online dispute began with a DAY6 K-pop concert in Kuala Lumpur on 31 January 2026. A South Korean fan known as a fansite master brought a professional long-lens camera into the concert area, even though event rules explicitly prohibited large cameras for audience comfort and copyright protection.

Footage of the incident spread widely on social media and drew criticism from local fans and other Southeast Asian netizens, who saw it as disrespect for local rules. The conversation escalated when some South Korean netizens responded defensively in ways that were viewed as offensive and stereotype-laden toward Southeast Asian people.

Several comments targeted Southeast Asians’ economic conditions and physical appearance. Even a music video clip from an Indonesian group—shot in rice fields—was mocked as a symbol of poverty. Cultural stereotypes were delivered in a negative tone, fueling regional anger.

This “alliance” did not stop at criticism. Southeast Asian netizens countered with creative responses. Some posts highlighted natural Southeast Asian beauty without plastic surgery, while taking aim at beauty standards in South Korea. Satirical memes and the hashtag #SEAblings triggered thousands of posts and pushed the topic into trending territory on X.

Racist-leaning remarks are not a new issue. According to a US News & World Report ranking in 2023, South Korea placed 9th out of 79 countries for racism levels. A Segye Ilbo survey in 2020 found 69.1% of 207 foreign residents in South Korea had experienced discrimination—ranging from hostile stares (32.9%) and verbal insults (16.4%) to wage discrimination (10.6%).

South Korea’s National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK) also recorded that discrimination often correlates with the perceived economic status of a migrant’s home country. In its 2019 report, 56.8% of 310 migrant respondents said they faced discrimination due to nationality, and 36.9% due to their country’s economic level. The institution noted that treatment of foreigners is frequently shaped by perceptions of whether someone comes from a “developed” or “developing” country, as well as skin color. These data suggest a long-standing, structural dimension to discrimination against foreigners in South Korea.

The SEAblings phenomenon on X also attracted broader attention. Using Socindex (a big data engine from PT Nestara Teknologi Teradata), conversations between 11–17 February 2026 were monitored and found to be highly varied in how netizens reacted.

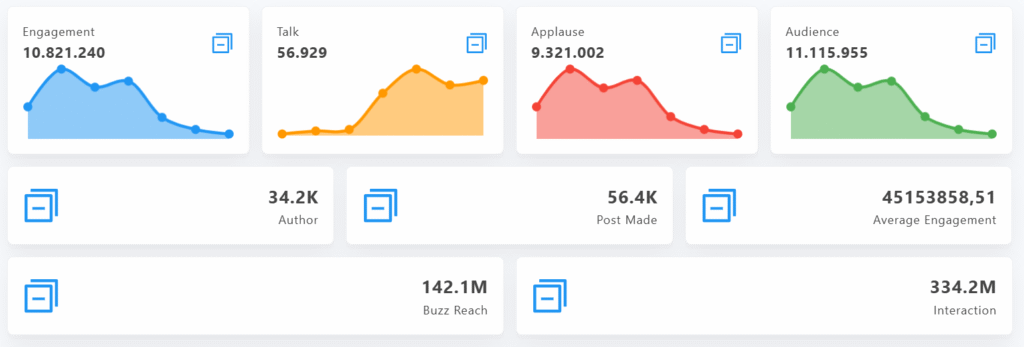

Monitoring results show that during this period, SEAblings was discussed by more than 34.2 thousand accounts, generating 56,929 conversations and 10.8 million engagements.

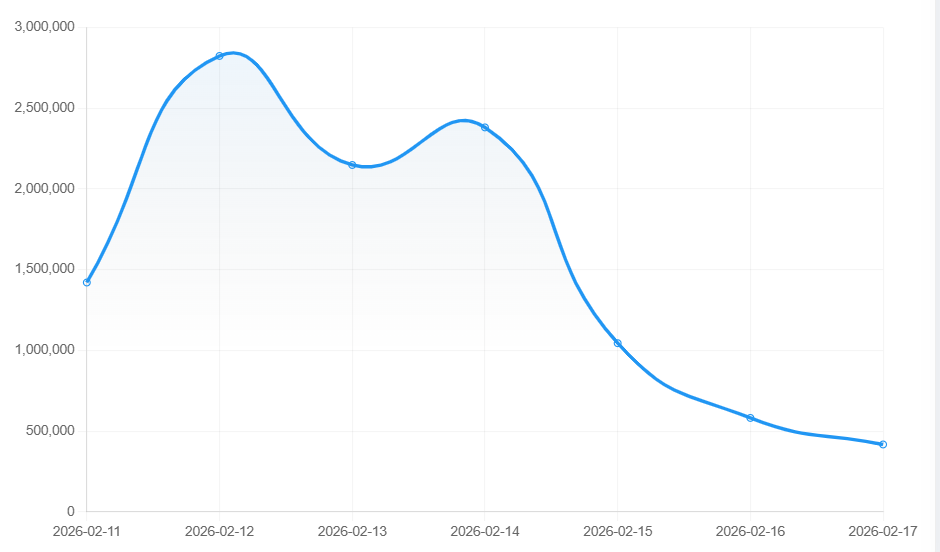

The peak occurred on 12 February 2026, when engagement reached 2.8 million. Discussion intensity remained relatively high until 14 February, before tapering off in the following days.

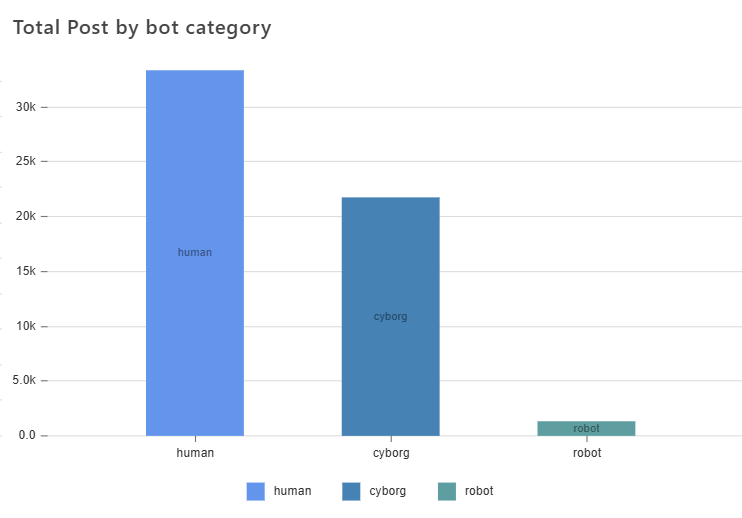

Socindex’s bot-score assessment indicates that the SEAblings conversation was organic. Accounts flagged as cyborgs or bots did not exceed human accounts, suggesting the discussion was dominated by genuine users.

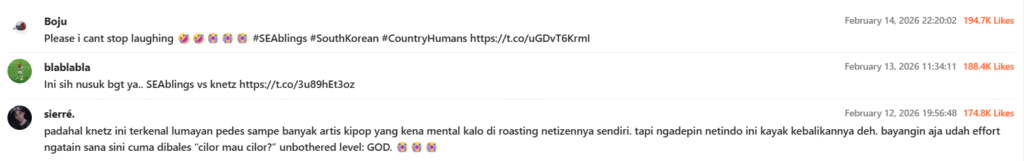

Based on top-like data, the three accounts receiving the most appreciation were @Boju3006, @vidvedvodvud, and @akunrambat. Their posts generally featured satire and use of the #SEAblings hashtag.

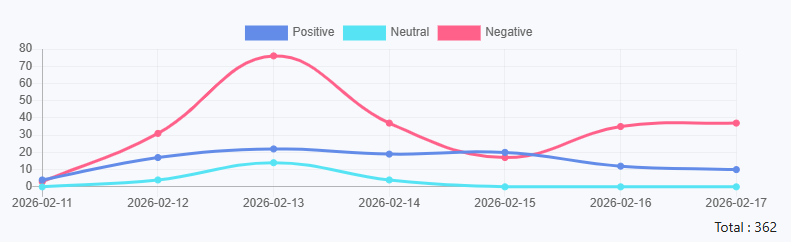

In mainstream media, SEAblings also received substantial coverage. Using Newstensity (PT Nestara Teknologi Teradata’s big data engine), monitoring for 11–17 February 2026 found 362 news articles, with peak coverage on 13 February 2026.

The word cloud suggests dominant keywords like “racism,” “war,” and “conflict.” This aligns with the most heavily reported angle: alleged racism by South Korean netizens and escalating tension between SEAblings and KNetz. Overall, coverage tended to lean negative in sentiment.

Gen Z in Southeast Asia has grown up in an era of social media where identity can be expressed openly and at scale. They are increasingly confident about showcasing local uniqueness—from cuisine to natural beauty standards that were previously dismissed or undervalued by outsiders.

SEAblings is not merely a viral trend that will fade with time. It signals the emergence of a more solid and confident Southeast Asian digital identity. If this collective energy is directed constructively, such regional solidarity could evolve into a meaningful force in the global digital landscape.

Lieutenant Colonel Teddy Indra Wijaya, the Cabinet Secretary of the Republic of Indonesia, is currently carrying three major roles at…

The government’s decision to appoint personnel from the Nutrition Fulfillment Service Unit (SPPG) as Government Employees with Work Agreements (PPPK),…

The evolution of marketing over the past few years has shown a major shift, especially as digital marketing becomes the…

Freedom of opinion and expression is a constitutional right protected by law. Today, the public’s channel for voicing disappointment toward…

In January 2026, the internet was shaken by the viral spread of a book titled “Broken Strings: Fragments of a…

The government has begun outlining the direction of the 2026 State Budget (APBN 2026) amid ongoing global economic uncertainty. Finance…

The Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Communication, Information, and Digital Affairs (Komdigi), has officially temporarily blocked the use of…

A few years ago, electric cars still felt like a far-off future. They were seen as expensive, futuristic in design,…

Hydrometeorological disasters hit three provinces in Sumatra—Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra. Tropical Cyclone Senyar, spinning in the Malacca Strait,…

The heavy rainfall in late November 2025 caused flash floods that submerged parts of Aceh, West Sumatra, and North Sumatra….