Pandji’s New Chapter of Comedy

Freedom of opinion and expression is a constitutional right protected by law. Today, the public’s channel for voicing disappointment toward…

During the English Civil War of 1642–1651, philosopher Thomas Hobbes lived in France and worked on his philosophical masterpiece Leviathan (1651). Hobbes argued that violence isn’t caused by exceptionally strong or aggressive people but because most people are weak and fearful. If you and I both fear one another, it makes sense for me to strike first or risk being attacked. The weak are as dangerous as the strong—perhaps more so—because they have more reason to fear.

Hobbes concluded that without authority, human life would be “nasty, brutish, and short.” Thus the state was born as Leviathan, a giant monster that governs and protects. John Locke, in Two Treatises of Government (1689), offered a different proposition: state power is merely the people’s mandate, and if that mandate is betrayed, the people have the right to resist.

Michel Foucault defined power differently. In Discipline and Punish (1975), he explained that power isn’t just present in weapons; it also operates through mechanisms, surveillance, discourse control and normalisation. In this perspective, Polri (the police) and TNI (the armed forces) are not merely officers but instruments of social discipline that shape how people can speak.

The 1998 reform taught a crucial lesson: civil supremacy. TNI was separated from Polri, with the military returning to defence and the police handling domestic security. Yet since the reform, TNI is often accused of peeking into civilian space—conducting covert intelligence operations, hidden business ventures and criminalisation. Polri, expected to be the civilian face of the state, has repeatedly been entangled in corruption, premeditated murder, excessive violence and eroded public accountability.

It’s no wonder that a series of demonstrations and civilian criminalisations since 25 August culminated in the 17+8 People’s Demands, reminding us of the 1998 trauma.

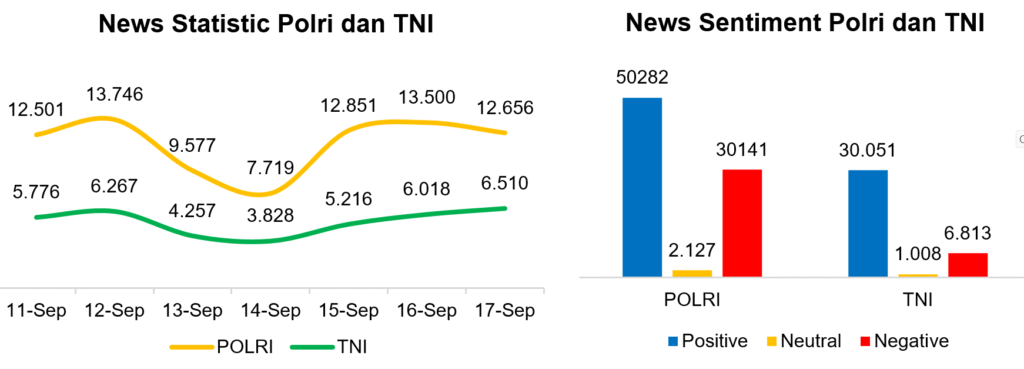

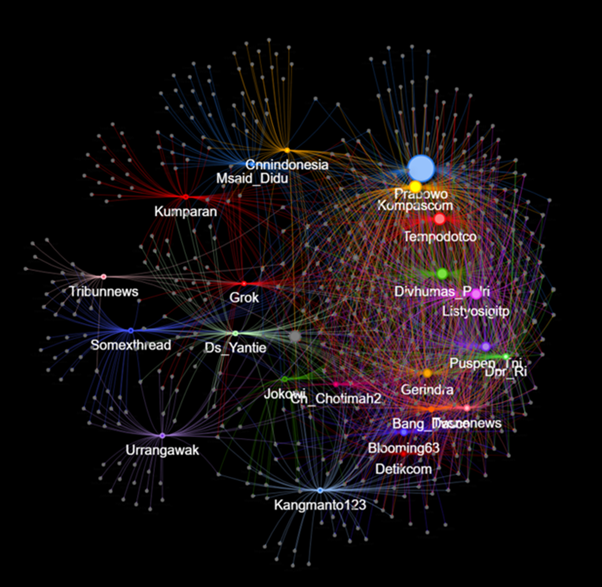

Media monitoring by Binokular’s Newstensity on TNI and Polri reveals how dominant the police are in public discourse. Between 11–17 September 2025, online, print and electronic media recorded 82,550 news items about Polri (69%), compared with 37,872 about TNI (31%). Coverage for both institutions peaked on 12 and 16 September. On 12 September, the media highlighted the Pamulang explosion in South Tangerang and calls for police reform; the peak on 16 September was driven by news about two Kopassus soldiers’ involvement in the kidnapping and murder of a bank branch head.

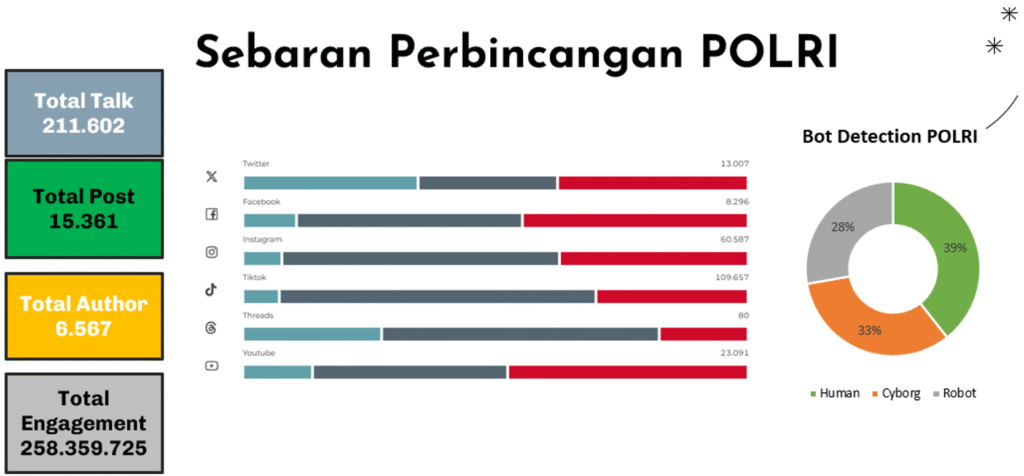

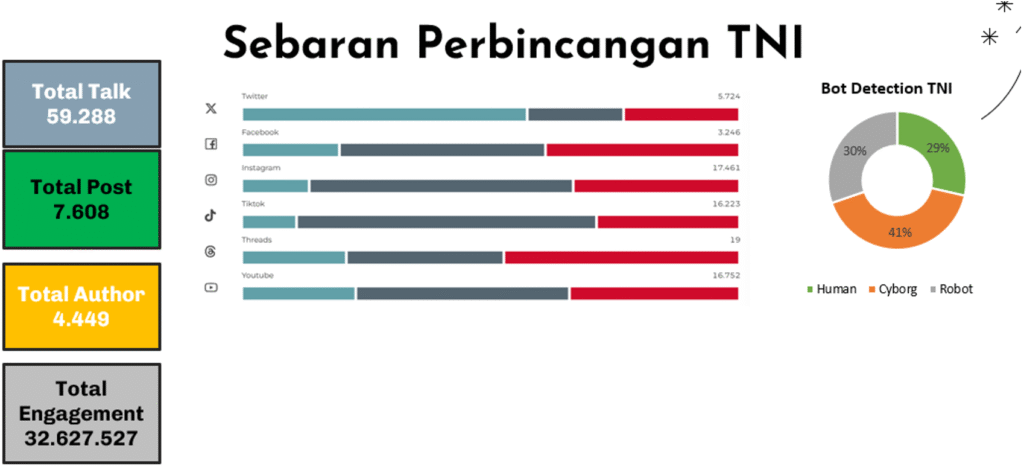

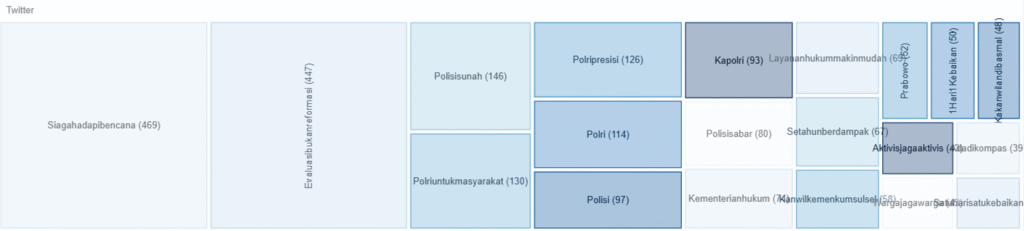

The same trend occurred on social media. Socindex, a social media monitoring, recorded that Polri was discussed 211,608 times (78%) with 258 million engagements, while TNI was mentioned 59,288 times (22%) with 32 million engagements. TikTok and Instagram were the main platforms for interaction.

Polri’s dominance in news and social‑media conversations shows the police now stand under intense public scrutiny. This is not only because of their role in law enforcement but also because the institution is seen as undergoing a legitimacy crisis. An Indikator Politik Indonesia survey conducted 17–20 May 2025 found TNI ranked first as the most trusted institution (95.8%), while Polri ranked ninth (72.2%) after the President, Attorney General’s Office, DPD, MPR, Supreme Court, Courts, and KPK.

Media monitoring found that among the 82,000 police-related news items, three topics generated positive coverage: managing floods in Bali on 9–10 September (3,449 news items); securing online-driver demonstrations on 17 September (1,649 news items); and the 2025 police mutation event at police headquarters on 12 September (254 news items).

Negative coverage came from calls for police reform (2,522 news items), rumours of replacing the national police chief (1,419), the presidential decree establishing a Police Reform Commission (816) and the ethics trial of five Brimob officers in the death of Affan (754).

Social media reflects public emotion. Socindex recorded 15,361 posts from 6,567 accounts discussing the issue. The numbers show Polri is discussed three times more than TNI, as if the police are more intrusive in daily life. Bot detection found 39% of Polri conversations are produced by human users.

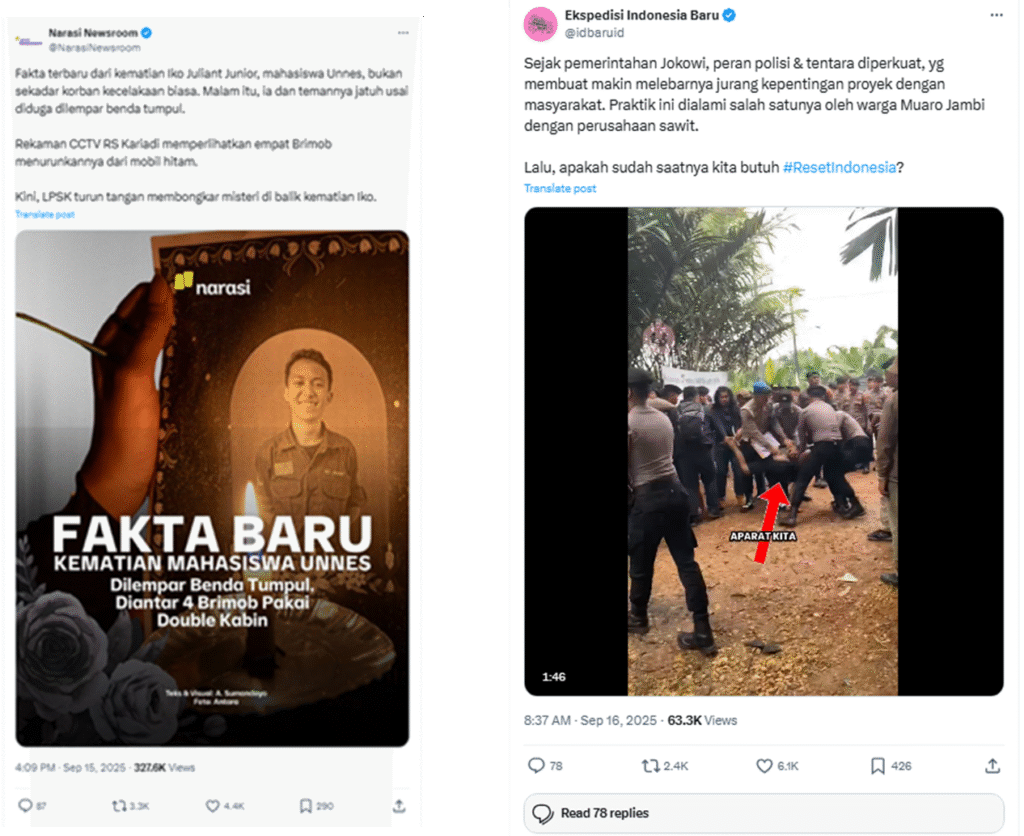

Three high‑attention issues underscore perceptions that the police often fail to protect the people. A post by @NarasiNewsroom—retweeted 3,368 times—highlighted the death of a University of Semarang student allegedly killed by a blunt object, not an accident. Another high‑engagement post by @idbaruid argued that the police and military have been strengthened since President Joko Widodo’s administration. Posts about the reduction of the death sentence for Ferdy Sambo to life imprisonment also reignited debate.

These figures reveal one thing: the crisis of police legitimacy is a central public concern. Sociologist Alex Vitale, in The End of Policing (2017), writes that the institution of policing is merely a symptom of a larger problem. “We need to stop funding brutal and ineffective policing,” he says, “and instead direct money toward social services for underserved communities”. To understand police funding, we must look at the broader economic and political structures, because the decision to delegate social problems to the police is a political decision. David Bayley in Police for the Future (1994) writes, “Police don’t prevent crime. This is one of the best-kept secrets of modern life. Experts know it, police know it, but the public doesn’t know it”.

While criticisms of Polri tend to be structural, attention toward TNI relates to the image of honour. Of the 37,872 news items, topics generating positive TNI coverage included flood relief in Bali, change‑of‑command ceremonies, plans for community‑based security (PAM Swakarsa) and TNI protecting the DPR building. Negative sentiment stemmed from issues such as two Kopassus soldiers involved in the kidnapping and murder of a bank branch head, the controversy over the TNI Cyber Team reporting Ferry Irwandi, the murder of a TNI member in Wonosobo and debate over revisions to the TNI Law.

On social media, Socindex recorded 7,608 posts from 4,449 accounts discussing TNI. Bot detection showed discussions about TNI are dominated by cyborg accounts (41%)—a mix of human and bot posts—while only 29% are from purely human accounts. This indicates TNI issues are more “shaped” or controlled by non‑organic accounts compared with Polri discussions, which come more from real user experiences.

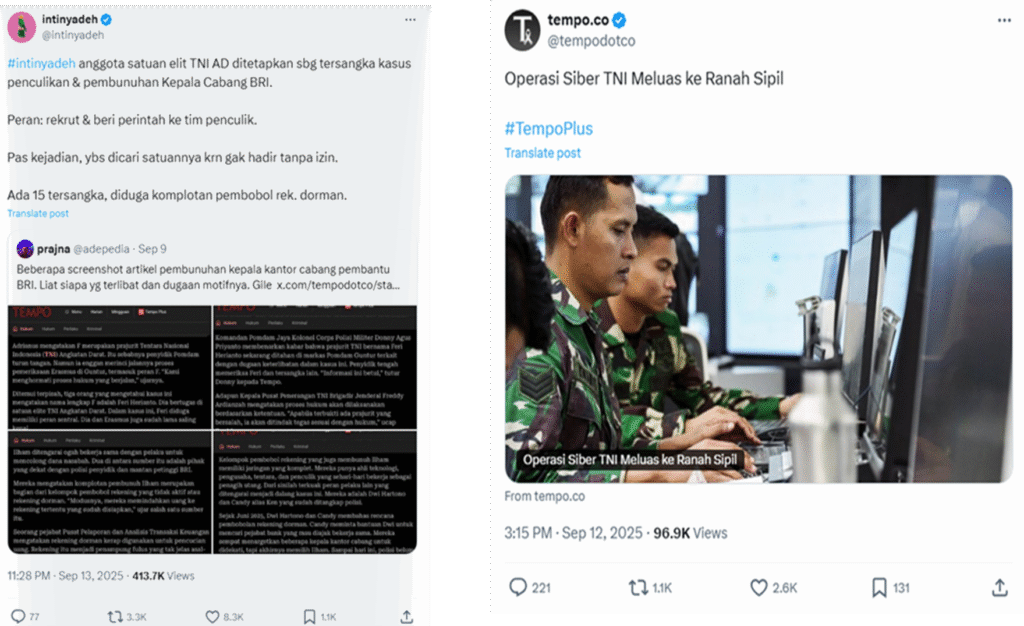

Netizens focused on two main topics. First, the TNI soldiers’ involvement in the bank branch head’s murder, posted by @intinyadeh—retweeted 3,304 times. Second, the controversy over the TNI Cyber Team reporting Ferry Irwandi, fuelled by a post from @tempodotco about the expansion of TNI’s cyber operations into civilian space, which garnered 2,653 likes. Ferry’s own Instagram post received 515,369 likes.

Another widely shared video by @official.ntv on TikTok showed defence expert Connie Rahakundini Bakrie arguing that reporting Ferry undermines TNI’s institution.

The TNI Cyber Team reported YouTuber and Malaka Project founder Ferry Irwandi to Jakarta Police. TNI Cyber Commander Juinta Omboh Sembiring alleged that Ferry committed a crime. Critics argue this violates Constitutional Court Decision 105/PUU‑XXII/2024, which exempts government institutions and corporations from being complainants in defamation cases.

Amnesty International said the action blurs the line between military duties and civilian affairs, noting that Article 7 of the 2025 TNI Law states the military helps defend against cyber threats, not persecutes citizens for criticism.

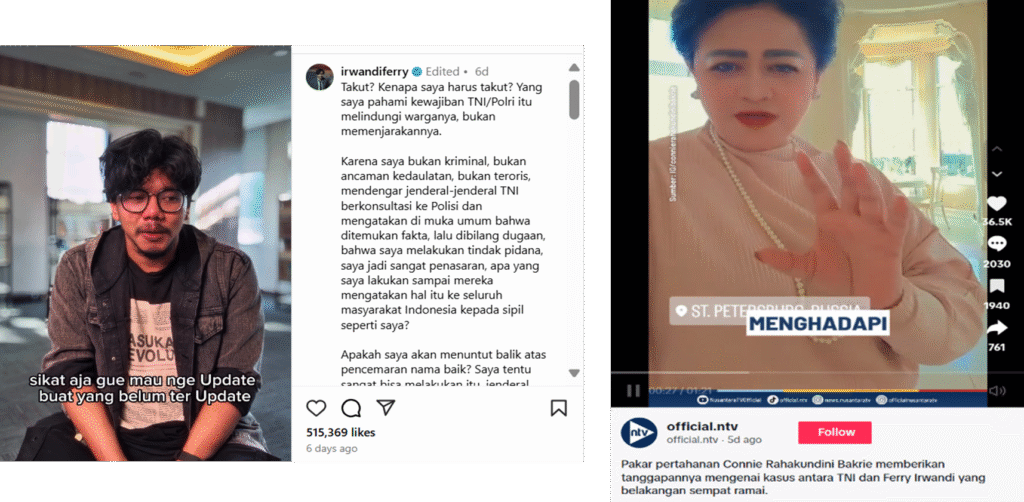

Social Network Analysis shows that the personal accounts most mentioned in conversations about Polri and TNI are @Prabowo, @Listyosigitp (the police chief) and @Jokowi. The most‑mentioned official accounts are @Divhumas_Polri, @Puspen_Tni and @Dpr_Ri.

Influencers such as @Msaid_Didu, @Ds_Yantie, @Urrangawa, @Ch_Chotimah2 and @Kangmanto123 also stand out. For instance, @Msaid_Didu is frequently cited in discussions about retired TNI officers’ suggestions to remove Gibran. However, this narrative is countered by content praising police performance under the hashtag #EvaluasiBukanReformasi Pertahankan Supremasi Sipil, especially from @blooming63.

@Ds_Yantie receives many mentions about the rotation of 27 police generals, suspected by netizens as an effort to strengthen “Termul” (a coalition) ahead of any police chief change. @Urrangawa appears in conversations about statements from State Secretary Prasetyo Hadi and Deputy DPR Speaker Sufmi Dasco Ahmad emphasising that President Prabowo never sent a presidential letter regarding replacing the police chief.

In 1998, after Soeharto’s fall, the people demanded two things: separating TNI from Polri—leading to Law 34/2004 on TNI and Law 2/2002 on Polri—and ending ABRI’s dual role, so the military could no longer engage in politics and would focus on defence.

Based on the findings above, we can conclude that whereas in 1998 people feared the military more, today they are more critical and suspicious of the police. Fear in 1998 was direct and brutal; suspicion in 2025 is complex—concerned not only with violence but also political manipulation, technology and image. Polri issues are structural and long‑term, while TNI issues are sporadic but dangerous because they encroach on civilian space.

The research also finds that the public seems to trust social‑media conversations more than conventional media narratives. Media tend to present Polri as the main face of security issues, whereas social media underscores the legitimacy crisis. High engagement and influencer roles on social networks highlight this shift. As Foucault noted, power is not just about who holds weapons but who controls discourse. In this context, people are trying to take control of the narrative through demonstrations, social media and open criticism.

Ultimately, TNI and Polri, despite their controversies, remain part of the national house. But that house will collapse if its occupants oppress each other. Let the people speak; let democracy be a mirror, not a threat. A healthy nation is not one that is silent, but one that bravely listens—even when others have yet to speak.

Writer: Hans Hayon (Newstensity), Ilustrator: Aan K. Riyadi

Freedom of opinion and expression is a constitutional right protected by law. Today, the public’s channel for voicing disappointment toward…

In January 2026, the internet was shaken by the viral spread of a book titled “Broken Strings: Fragments of a…

The government has begun outlining the direction of the 2026 State Budget (APBN 2026) amid ongoing global economic uncertainty. Finance…

The Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Communication, Information, and Digital Affairs (Komdigi), has officially temporarily blocked the use of…

A few years ago, electric cars still felt like a far-off future. They were seen as expensive, futuristic in design,…

Hydrometeorological disasters hit three provinces in Sumatra—Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra. Tropical Cyclone Senyar, spinning in the Malacca Strait,…

The heavy rainfall in late November 2025 caused flash floods that submerged parts of Aceh, West Sumatra, and North Sumatra….

When we consider people’s decisions today—what to buy, what issues to trust, and which trends to follow—one thing often triggers…

Finance Minister Purbaya Yudhi Sadewa underscored the government’s uncompromising stance against illegal used-clothing imports, which he stated have harmed the…

Over the past month, Indonesia’s political elites, economists, and the general public were stirred by a statement from Finance Minister…